For an article in the New York Times, technology writer Brian X. Chen wore a sleep-tracker for a couple of weeks. He reports:

Ultimately, the technology did not help me sleep more. It didn’t reveal anything that I didn’t already know, which is that I average about five and a half hours of slumber a night. And the data did not help me answer what I should do about my particular sleep problems. In fact, I’ve felt grumpier since I started these tests.

Source: The Sad Truth About Sleep-Tracking Devices and Apps

Breaking news: Looking at your power bill every month does not cut your electricity consumption! Checking your speedometer does not slow down your car! Tracking your spending does not make you rich!

I’ve been using a sleep tracker (the Oura ring) since December. Neither wearing the ring nor checking the reports I get has increased the amount of sleep I got. However, I have learned a lot about how to get more and better sleep.

Probably the most useful thing I’ve learned is that the standard advice that you should have supper at least three hours before bedtime isn’t sufficient for me: I sleep much better if I finish supper at least four hours before I lie down to go to sleep.

That’s actually a specific example of my larger point: A sleep tracker makes it easy to run little experiments and quickly see the results.

My intuition as to whether I got a good night’s sleep is an excellent guide (as I suspect it is for most people). But even a good intuition isn’t always enough to run a good experiment, and this is an example of that. Although the Oura ring’s report isn’t better than my own intuition, it provided some specific information that led me to that particular insight: On days when I had a late supper, my sleep quality was quite poor for the first couple hours of sleep, a pattern that I didn’t see on days when I had an early supper.

I’ve used it to run other experiments. For example, it appears that I get more deep sleep on days when I have only one drink than on days when I have two. (This is very sad news, and will have to be confirmed by many more experiments before I use it to modify my behavior—but at least I can run the experiments.)

After a rough patch last fall (which is what prompted me to order the Oura ring), I’m actually sleeping pretty well now, so I’m not aggressively running new experiments to try and improve my sleep. I am, however, paying attention when a natural experiment presents itself. For example, we generally sleep with the windows open all summer. Over the next two nights that will probably produce sleeping temperatures in the 70s, whereas over following several nights I’ll get to enjoy sleeping temperatures in the 60s. I know from experience that the cooler temperatures will produce better sleep, but the Oura ring will give me detailed metrics that will let me investigate if there’s an optimal temperature—information that may be very useful in the winter for deciding how to adjust the thermostat.

That’s the value of the ring for me: It lets me run experiments of specific sleep interventions, and gives me results that are more fine-grained than just a general sense as to whether I slept well or not.

Here’s one more natural experiment. I observed decades ago that I need more sleep in the winter than I do in the summer. I can now put a couple of numbers on that.

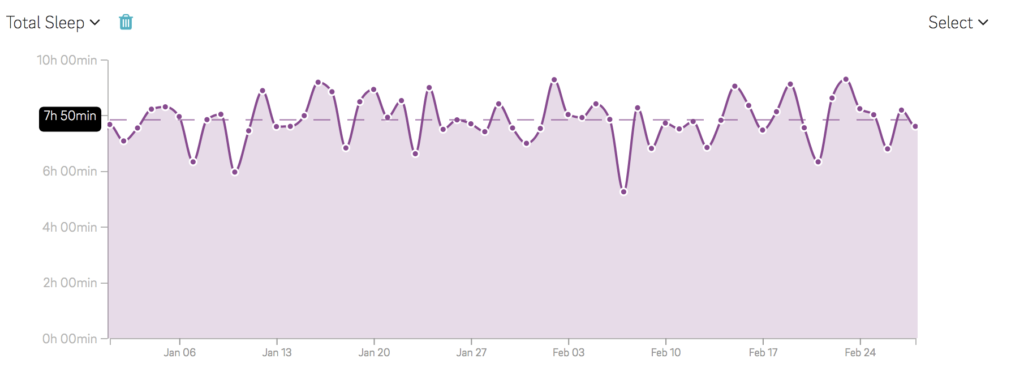

Here’s my total sleep each day in January and February this year. The report from the Oura ring lets me see that I averaged 7 h 50 min of sleep each night:

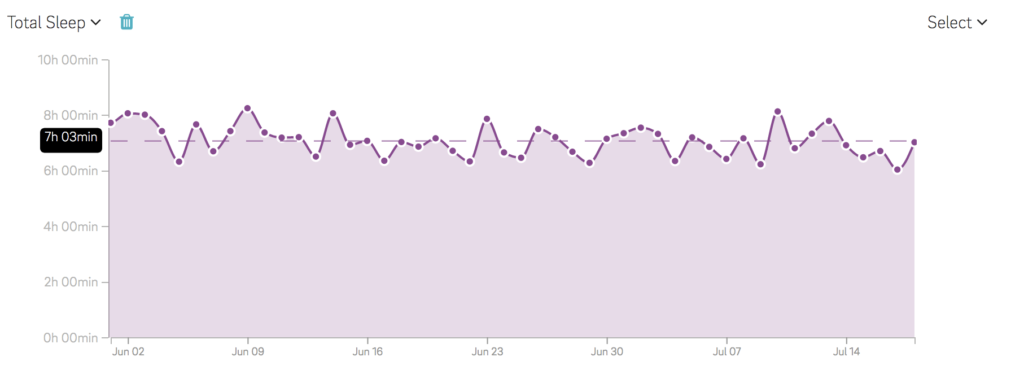

Here’s my total sleep each day from June 1st through last night. I can see that I averaged 7 h 03 min of sleep each night:

I’ve perceived each period as being roughly equally good in terms of getting “enough” sleep, so I’m inclined to think of the 47 minute decrease in sleep as being a decrease in the amount of sleep I need when the days are long and sunny and I’m getting plenty of fresh air and exposure to nature. In the winter I need darn near 8 hours of sleep per night. In the summer I can get by fine on just over 7.

That information doesn’t make me sleep better, but it’s still useful (even if it just confirms something I’ve known for a long time).

In other breaking news recently published in the science journal “Duh!”: Stepping on the bathroom scale every morning neither increases your muscle mass nor reduces your fat mass!