“This isn’t what we voted for!” scream a bunch of American racists and fascists who voted for exactly this.

Category: Economics

We know what happens when the Fed “looks through” one-off price hikes

Many politicians and financial analyst types are suggesting that the Fed should “look through” tariff-induced price hikes. Superficially this makes sense, because a one-time cost increase is not the same thing as inflation. Unfortunately, we know that the results are bad.

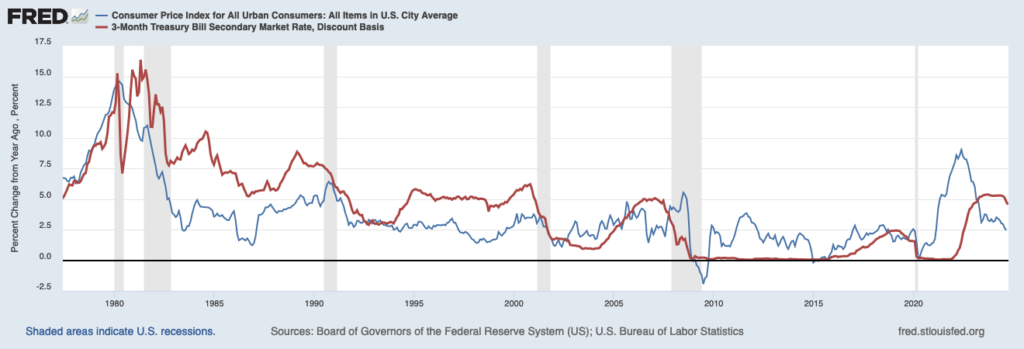

The example I’m thinking of is the price shock from much higher oil prices due to the 1973 OPEC oil embargo. As that price shock moved through the economy, first oil prices went up, then gasoline prices went up, but very shortly all prices moved up, because every business faced higher energy costs, and needed to pass at least a fraction of them forward. And then, of course, all the businesses that bought things from those businesses needed to raise their prices further, and workers started demanding higher wages because their costs were going up.

The Federal Reserve tried to “look through” that price shock, not raising interest rates, even though prices were rising. As I say, this makes sense. The one-time price shock will move through the economy, raising many prices by various amounts (depending on how much the inputs for each particular item increase in cost, and the market constraints on price increases for each particular item). Once that all works through the economy, the prices increases should stop.

In fact, raising interest rates could easily make things worse, because the cost of credit is another cost to nearly all businesses, so it’s just another expense that they have to pass on, and it’s a cost to employees, that they’ll want to recover in wage negotiations.

But we know what happened: Inflation rose enough that the Fed eventually decided that it needed to raise interest rates. Higher interest rates hurt the economy, threatening to produce a recession. The Fed cut interest rates to head off the threatened recession, which led to inflation, which led to the Fed raising rates again, etc.

The result was the stagflation of the 1970s, which only ended when new Fed chairman Paul Volker raised rates high enough to produce a severe recession, and then kept them high for long enough to wring the inflation out of the economy.

To me it’s clear that “looking through” the “one-time” price shock of higher tariffs will produce the same result. The Fed can probably mitigate it by holding rates at their current levels until the price shock works its way through the economy (which will probably take a least a year, because many prices (wages, rents, etc.) are only renegotiated annually), and only cut rates after price increases settle back down to close to the Fed’s 2% target.

I assume the Fed governors know this. Do they have the courage to take the right action? Only time will tell.

2025-04-03 07:24

Some financial commentators are suggesting that the hit to the economy from the new tariffs will push the Fed to lower interest rates, but I don’t see it. The tariffs will push up prices, so the Fed will feel it needs to stick with higher rates for longer.

The result will be exactly as I forecast months ago: the coming stagflation.

Our new upcoming stagflation

A group of friends and I agreed last week that the most likely result of the most likely policies coming out of this administration is stagflation.

Talking about it reminded me of the Wise Bread post I wrote All about stagflation, so I re-read that. I think has held up pretty well, even though circumstances (financial crisis followed by a pandemic) meant that things didn’t play out as I’d expected. Even so, I think the analysis of how to produce a stagflation is right on: raise interest rates to bring down inflation, but then panic when it’s clear that you’re in danger of producing a recession and cut rates before you’ve gotten inflation under control; repeat until you have high inflation and a recession.

That is, stagflation is usually the result of a timid Fed, that’s afraid to do its job.

The thing is, the policies that I see coming (tariffs and tax cuts) will produce stagflation even if the Fed does a great job. The tariffs directly raise prices, and the tax cuts (through increased deficits) raise interest rates, producing a recession.

In the Wise Bread article I warn that it’s tough to position your investments for stagflation. The reason is that inflation makes the money worth less (helping people with debts, but hurting people with money), while the recession hurts people with debts and people with investments.

Upon reflection though, I don’t think it’s quite that bad. In fact, it’s really just regular good financial advice:

- Avoid debt (you’ll get crushed by a recession faster than you’ll get rescued by inflation).

- To the extent that you have assets, move them into cash (initially you’ll get screwed by inflation, but pretty soon rising interest rates will save you).

- Limit your investments in stocks, and especially limit your investments in your own business (both much too likely to get crushed by recession).

Basically: live within your means and stay liquid.

Struggling with Schadenfreude

I don’t think of myself as someone who wishes ill for others. I genuinely do not wish for anyone to come to harm. But I’m struggling just a bit with schadenfreude right now.

Take, as an example, the wildfires in California. As I mentioned a couple of weeks ago, these fire events were not just entirely foreseeable; they were actually foreseen forty years ago. And yet, there are tens of thousands of people who apparently made the calculation that the views from a house on a hillside at the urban-chaparral interface were so good it was worth taking the risk—and especially so, given that a large fraction of the costs of fighting those fires, and insuring against financial loss, could be spread to other people. People like me.

I think I’m allowed a bit of, “I hope you are enjoying the entirely foreseeable consequences of your choices.”

As another example, take the snow about to hit New Orleans:

By Tuesday, the winter storm will drop freezing rain, sleet and likely several inches of snow onto south Louisiana, including in New Orleans, Metairie, Slidell, Baton Rouge and Lafayette.

I have to admit that when people in red states face an extreme weather event that’s entirely to be expected, a certain part of me thinks, “Well, you could have voted for politicians and policies that would have greatly ameliorated climate change, but you didn’t. Enjoy the entirely foreseeable consequences of those choices.”

And, as a non-climate example, apparently a lot of black and brown male voters refused to vote for Kamala Harris. I suspect many of them will be surprised and saddened by the utterly predictable deportations of friends, family members, neighbors, coworkers, and employees over the next few years. And I will be very sad about that—sad for the people deported and their friends and family, and also about the dreadful police actions that will be required to make them happen. But I hope I will be excused from feeling no sympathy for the bosses who find themselves having to pay up to get workers who haven’t been deported, and very little sympathy for the people who voted for these policies and find that everything they want to buy costs more.

“Welcome to the entirely foreseeable consequences of your actions as well.”

2025-01-19 07:25

I had one of these accounts whose rate never went up as interest rates rose. I kept it longer than I should have, but I eventually switched banks. (I wasn’t going to switch to their higher-rate “Performance Savings,” because screw that. They can pay a market rate, or they can lose my business.)

[Capital One] operated two separate, nearly identically named account options — 360 Savings and 360 Performance Savings — and forbade its employees to volunteer information about or marketing… the higher-paying one, to existing customers.

Source: NYT

2025-01-09 08:26

I lived in Los Angeles briefly in 1986. While I lived there, my dad sent me this book:

It talked about landscaping to minimize fire, flood, and mudslide risk, but my key takeaway was, “Only a moron would live in Southern California,” and I moved away before the end of the year.

It was a government publication, so the PDF is available: https://www.fs.usda.gov/psw/publications/documents/psw_gtr067/psw_gtr067.pdf

2024-12-24 07:18

I keep hearing this stupid ad which, due to an infelicitous pause in the audio, seems to say, “Before you invest carefully, consider the funds objectives, risks, charges and expenses.” I always want to respond, “Before you invest carelessly, don’t bother.”

Inflation and interest rates in 2025 and beyond

Let me start by saying that, judging from his previous term, most of what the incoming president says has no particular bearing on what he’s going to do. But I think a few trends look likely enough that it’s worth thinking about the results on the dollar’s value.

The things I’m thinking of are tariffs and tax cuts, which I expect to lead to higher inflation and larger deficits, both of which will lead to higher interest rates.

Tariffs

The president can impose tariffs on his own, with no need for congressional action. Whether we’ll get the proposed 60% tariffs on Chinese goods, or whether that’s just a bargaining chip, I have no idea. But I think some amount of tariff increase will be imposed, which will feed through directly to higher prices.

That’s not to say that tariffs are necessarily bad (although usually they are). But they do feed through to higher prices.

Tax cuts

Tax cuts need to get through Congress. If the Republicans get the House as well as the Senate, it’s highly likely that legislation will preserve the 2017 tax cuts set to expire next year, and probably some additional tax cuts, such as a much lower rate on corporate income. It’s also possible that we’ll see the proposals to cut tax rates on tip income and on overtime pay enacted, although I doubt it. (The incoming president only cares about his own taxes, not about those of random working-class folks.)

The main thing taxes cuts will do is dramatically increase the deficit. The tariffs will bring in some countervailing revenue, but not nearly enough to fill the gap.

Other things that raise inflation and cut revenue

There are all kinds of other proposals that were bandied about during the campaign, such as deporting millions of immigrants, that raise costs both for the government, leading to higher deficits (the labor and logistics both cost money, and not a little) and for employers (they’re employing the immigrants because their wages are lower), which they will try to offset with higher prices.

What this means for our money

Rising costs will feed directly into higher prices, which is going to look like inflation to the Fed, so I think we can expect short-term interest rates (the ones controlled by the Fed) to get stuck as a higher level than we’d otherwise have seen.

At the same time, lower taxes will mean lower government revenues, leading to larger deficits. For years now, the government has been able to get away with rising deficits, but I doubt if the next administration will have as much success in this area. (Why not deserves a post of its own.)

My expectation is that higher deficits will mean higher long-term interest rates, as Treasury buyers insist on higher rates to reward the risks that they’re taking.

So: Higher short rates and higher long rates, along with higher inflation.

What to do

I had already been expecting inflation rates to stick higher than the market has been expecting, so I’d been looking at investing in TIPS (treasury securities whose value is adjusted for inflation). I’m still planning on doing so, but not with as much money as I’d been thinking of, for two reasons.

First, I’d been assuming that money market rates would come down, as the Fed lowered short-term rates. Now that I think short-term rates won’t come down as much or as fast, I’m thinking I can just keep more money in cash, and still earn a reasonable return.

Second, I’d been assuming that treasury securities would definitely pay out—the U.S. has been good for its debts since Alexander Hamilton was the Treasury Secretary. But the incoming president has very odd ideas about bankruptcy. As near as I can tell, he figures the smart move is to borrow as much as possible, and then declare bankruptcy, and then do it again. It worked for him, over and over again. I’m betting that Congress won’t go along with making the United States do the same, but I’m not sure of it.

Of course, if the United States does do that, the whole economy will go down, and my TIPS not getting paid will be the least of my problems.

2024-11-03 14:57

Cory Doctorow (@pluralistic@mamot.fr) writing for the economics journal “Duh!”:

I will never again devote my energies to building up an audience on a platform whose management can sever my relationship to that audience at will.