Yesterday we happened to get to Schnuck’s just as they were putting out packages of toilet paper, so we snagged two big packages.

I’m really bemused by what they are and are not out of. Onions were all gone, except a small number of organic white onions. Ground beef all gone (but we snagged a pound of ground bison, which I figure will be much better anyway, at almost twice the price of beef, of course). All the other stuff we buy routinely was there.

I can’t help but wonder what someone from the 1700s would say if we told them that people were panic-buying in the face of a plague outbreak, and then showed them a grocery store where all you could get was unlimited fruit (including tropical fruit), unlimited veggies (except onions), unlimited amounts of all the premium cuts of meat, and unlimited staples like flour, sugar, rice, beans, etc.

We also got a big carton of beer and a big bottle of whiskey, in case of emergency.

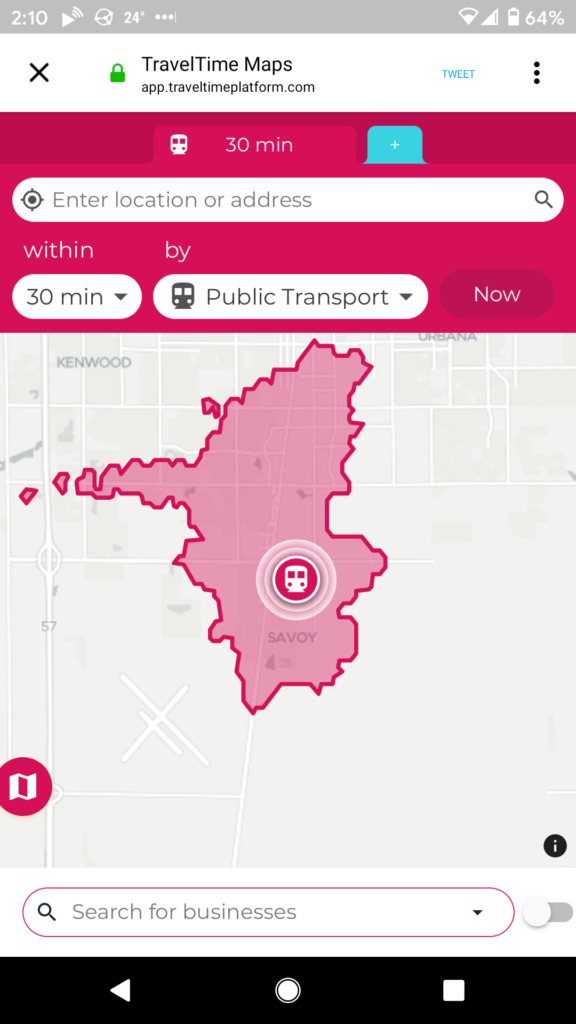

Do municipal taxes bring in enough money to maintain our urban and suburban infrastructure? In the densest urban areas, probably yes. Otherwise, generally no.

Do municipal taxes bring in enough money to maintain our urban and suburban infrastructure? In the densest urban areas, probably yes. Otherwise, generally no.