An excellent piece by @doctorow. Not just clear, accurate economics, it also gets at the heart of why I always wanted to be a rentier:

By contrast, rentiers are insulated from competition.

Source: Pluralistic

An excellent piece by @doctorow. Not just clear, accurate economics, it also gets at the heart of why I always wanted to be a rentier:

By contrast, rentiers are insulated from competition.

Source: Pluralistic

Maybe this will be the nail in the coffin of the idea that any surplus capacity is wealth that should be in the hands of the 1%, rather than an essential buffer against catastrophe.

I have always been an optimizer. I spend way, way too much time, energy, and attention optimizing things. Which is, you know, fine, even though my net benefit is small or zero, largely because I don’t focus my optimization efforts in places where I get the biggest payoff. (I’d say that I don’t optimize my optimization efforts, but I don’t want to tempt my brain into trying to do that. It would not end well.)

One place where my optimization efforts did end well has been in optimizing things for life under late-stage capitalism.

I was helped by a couple of lucky coincidences and a bit of lucky timing.

Purely because I enjoyed doing software, I became a software engineer at the dawn of the personal computer era, which gave me a chance to earn a good salary straight out of college, a salary that grew faster than my expenses for most of the next 25 years.

Whether because of my upbringing or my genes (my grandfather was a banker), I liked thinking about and playing with money, which meant that I was doing my best to save and invest during a period when ordinary people could easily earn outsized investment returns.

It worked out very well for me. I’m as well positioned as anyone who isn’t in the 1% to do okay in late-stage capitalism. (Frankly, better positioned than a lot of the 1%, who find it easy to imagine that they deserve the lifestyles of the 0.1%, and if they live like they imagine they should will quickly ruin their lives.)

This whole post was prompted by a great article that looks mainly at the efforts women make to optimize themselves under the overlapping constraints of health, fitness, appearance, and financial success in the modern economy. Highly recommended—insightful and daunting, but also funny:

It’s very easy, under conditions of artificial but continually escalating obligation, to find yourself organizing your life around practices you find ridiculous and possibly indefensible…. But today, in an economy defined by precarity, more of what was merely stupid and adaptive has turned stupid and compulsory.

Athleisure, barre and kale: the tyranny of the ideal woman by Jia Tolentino

One focus of that article is on “fitness.” I put fitness in quotes because of the way, especially for women, so much of fitness is actually about appearance. Perhaps because I’m not a woman—also perhaps because I’m already married, and because I’m older—my own perspective on fitness has gotten very literal: I want my body to be fit for purpose—fit for a set of purposes which I have chosen. I want to be able to do certain things because I have found the capability to be useful. (I also want to be able to do certain things that I can’t do, because I imagine that the capability would be useful, and much of the exercise I do now is intended to achieve those capabilities.)

In a sense, optimizing for fitness is really neither here nor there as far as optimizing for late-stage capitalism, which is mostly about money. And yet, really it is. My fitness suffered during the period I was working a regular job. Getting fit and staying fit takes time. To a modest extent, you can substitute money for time—you can pay up for the fancy gym where the equipment you want to use is more available, or take a job that doesn’t pay as much but allows you to squeeze in a midday run. But now we’re right where we started: optimizing for life in late-stage capitalism.

I should say that I’m delighted with how well my life has turned out. If I’d had any idea how little I could spend and still have everything I really want, or how early I’d have saved up enough money to support that modest lifestyle, perhaps I could have avoided a lot of anxiety and unhappiness along the way. But who among us has such luck? And more to the point, maybe some of that anxiety and unhappiness were crucial to my making the choices I did that got me to where I am.

I worry just a bit about my irresistible impulse to optimize, but like everything else about me, it got me to where I am. And, as I say, I’m delighted to be here.

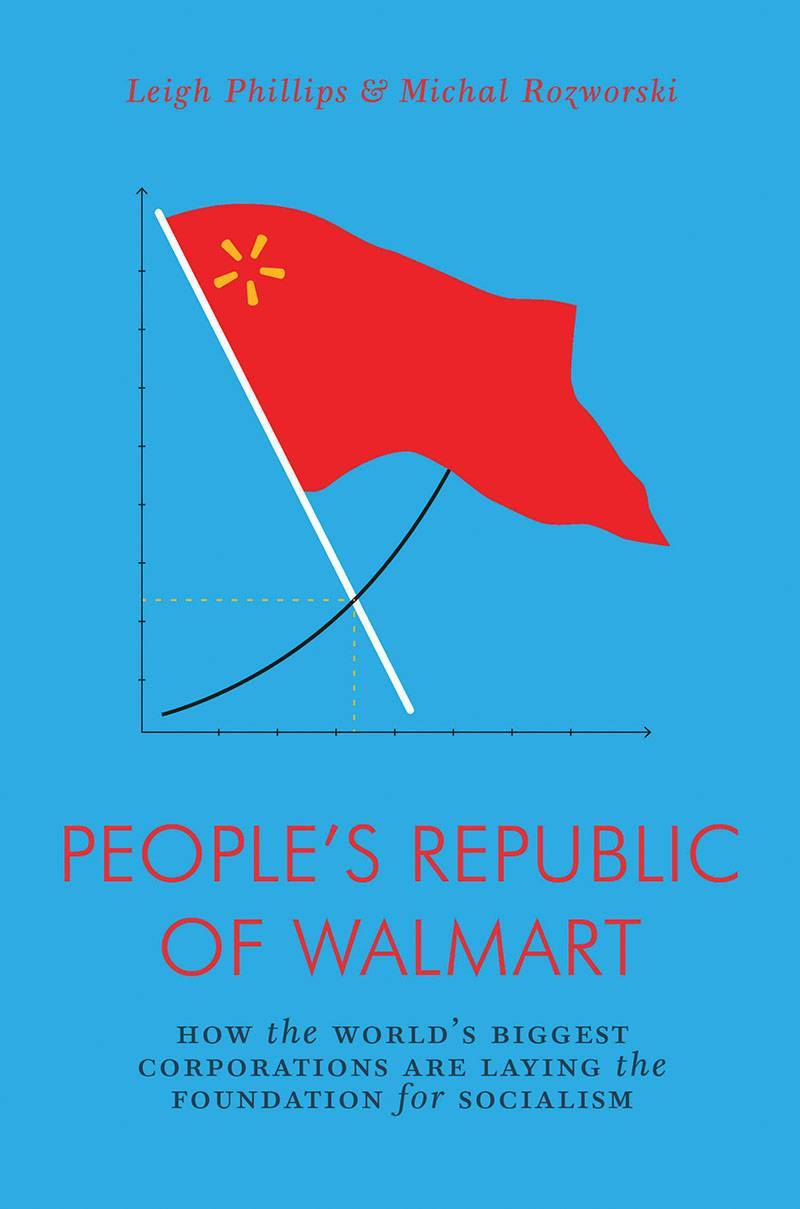

Very interesting and right up my alley: “fully automated luxury communism isn’t just science fiction: it’s a going concern with real evidence on the ground.” Via BoingBoing. h/t @limako

Blame the bosses, not the robots, when your job gets automated away. ‘Robots’ Are Not ‘Coming for Your Job’—Management Is