For a couple of years now I’ve been experimenting with time-restricted eating.

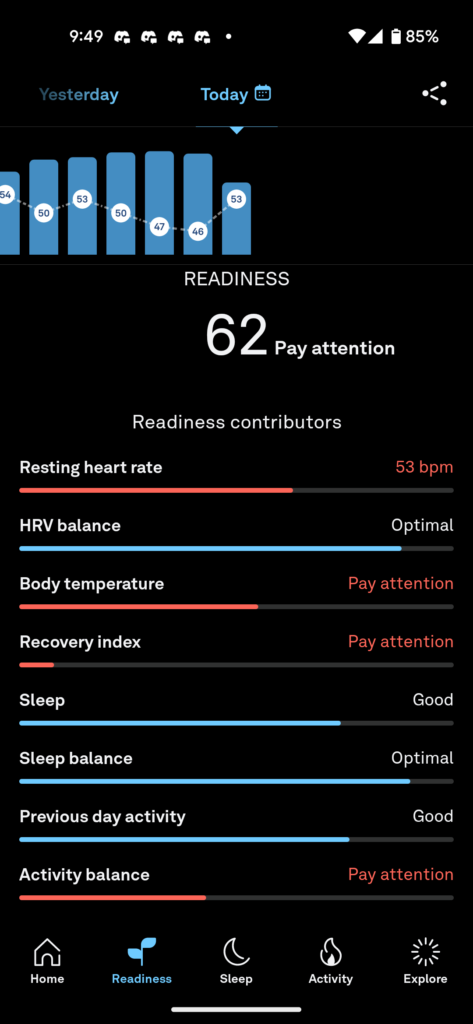

I guess I really started about a year and a half ago, after I got my Oura ring. One of the first things I noticed was that the early hours of my sleep were disrupted unless I had finished dinner at least 4 hours before bedtime. (This in contrast to the “common wisdom” that you want at least three hours between the last thing you eat and bedtime.)

Once I notice that I started pushing Jackie to arrange things so that we could finish supper at least 4 hours before we went to bed. The issue here was that while working at the bakery Jackie had gotten into the habit of getting up at 4:00 AM—because that’s when she needed to get up if she was going to be able to have coffee, breakfast, dress for work, and then spend most of an hour walking to work. As she has been so far unable to break herself of that habit, she finds herself very sleepy starting at about 8:00 PM. If you work out the math, you can see that we need to finish supper no later than 4:00 PM.

Jackie found herself somewhat daunted by the prospect of having to prepare lunch at mid-day, clean up the kitchen, and then prepare supper to serve at 3:00 PM so we could be done by 4:00 PM.

We experimented with various lunch/supper timings with limited success. But back in December, when Steven brought Lucy and his boys to visit, we fell into the habit of just having two meals a day. I went to his hotel for the breakfast that the hotel served to guests (Jackie made her usual breakfast at home), and then one of us (often, but not always, Jackie) prepared our main meal of the day sometime in the afternoon.

This turned out to work great, and Jackie and I have continued the practice since Steven and family departed. Jackie gets up at 4:00 AM as usual. (I tend to sleep until closer to 6:00 AM.) We linger over coffee, then have breakfast at 7:00 AM or so. Whatever we hope to get done in the day happens between 8:00 AM and 2:00 PM, at which point we have “dinner” consisting of our main meal of the day. We finish it by 3:00 PM or so.

(In these pandemic days we follow that up with a virtual happy hour with Steven and Lucy via Zoom, so we’re still consuming cocktails until 4:30 PM or so, but I try to make sure to limit both the carbs and the calories that late in the day. I’m hoping that eventually we’ll be able to arrange things such that happy hour doesn’t extended until so close to bedtime.)

Jackie and I usually enjoy some video entertainment in the evening, and then retire to read for a bit before 8:00 PM and time to go to sleep.

I’m sure that’s way more detail than a stranger could be interested in, but the gist is that our eating window is compressed to just 9 hours a day or so (from 7:00 AM until 4:00 PM), putting us within striking distance of a 16:8 time-restricted eating window.

And I have to say, it’s working pretty well. Jackie especially appreciates not having to prepare both lunch and dinner every day. Keeping my weight stable has been especially easy—if I’m hungry in the morning I fix a bigger omelette, if I’m hungry at mid-day I take a bigger serving of whatever Jackie is fixing, or just have something more (peanut butter, cottage cheese, jerky, protein powder, whatever). And if I’m not extra hungry, I just eat a regular breakfast and a regular mid-day meal.

The result has been that I easily get enough food, don’t overeat, get done eating four hours before bedtime, and spend nearly 16 hours per day in a fasted state, with all the attendant benefits described in the post linked just above. And as a bonus, Jackie doesn’t have to prepare two meals after breakfast.

Time-restricted eating: Highly recommended.