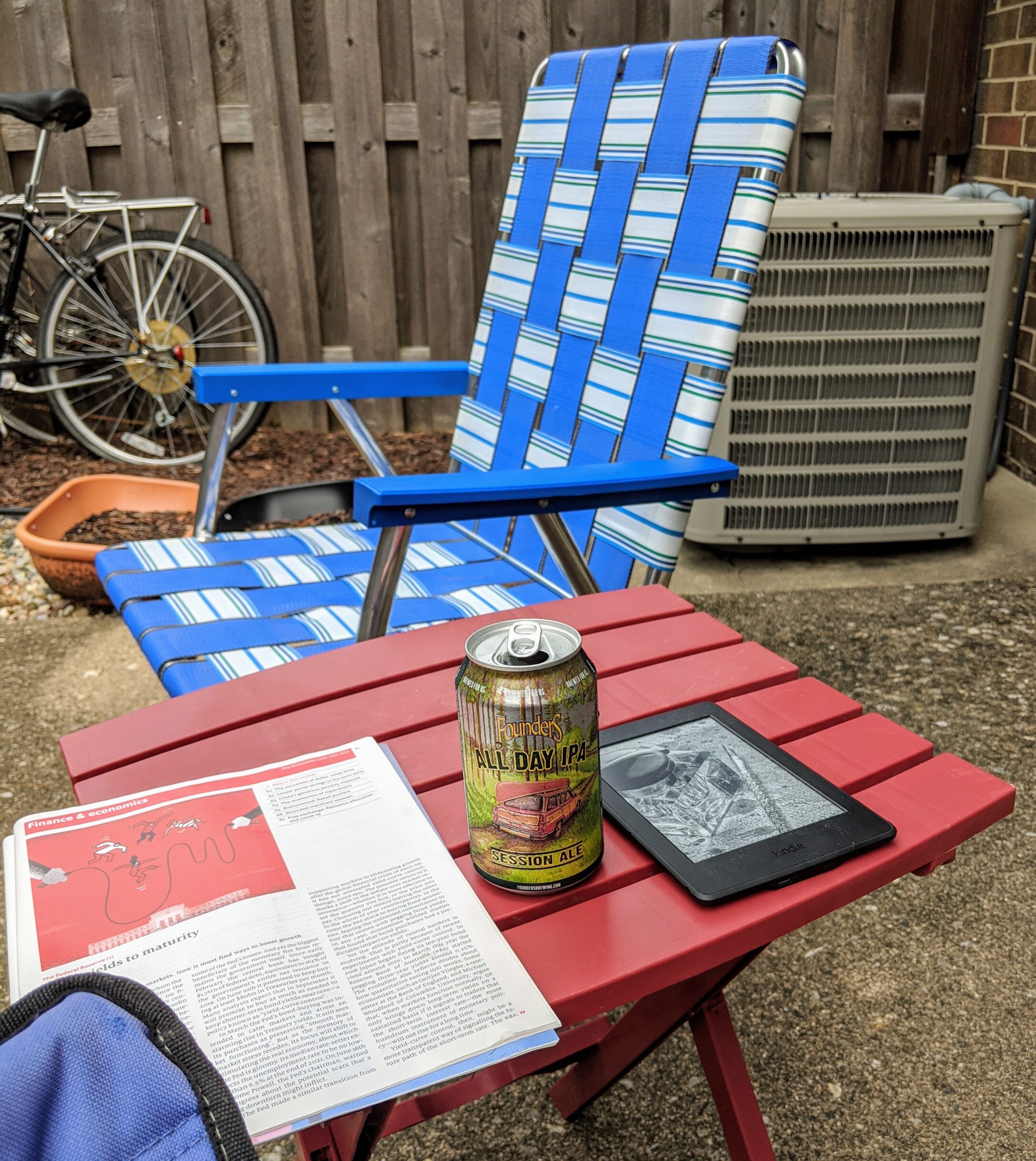

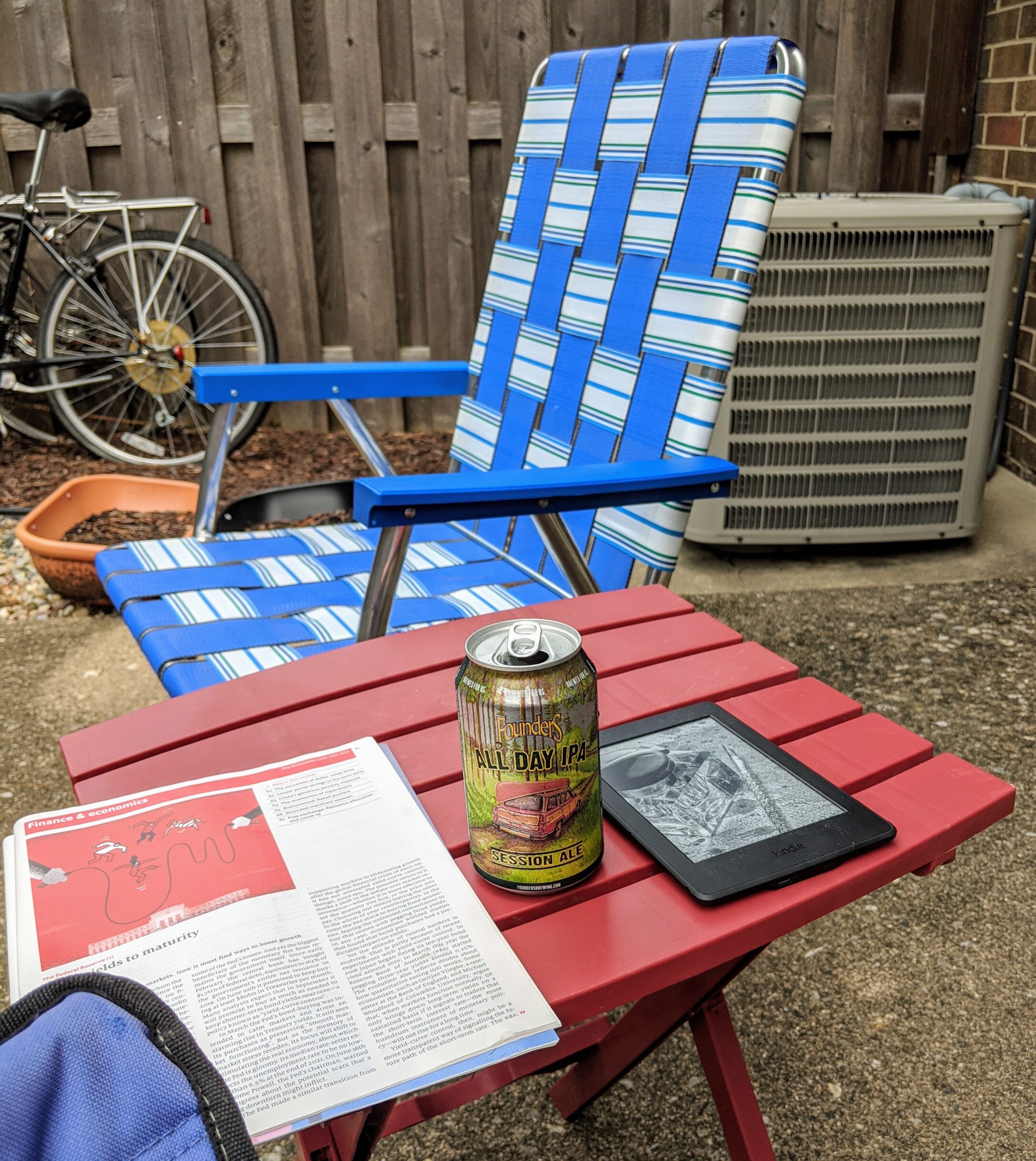

Sitting on the patio, drinking a beer and reading The Economist. Jackie is nearby, and expected to return. Kindle on standby for when Economist runs out.

Sitting on the patio, drinking a beer and reading The Economist. Jackie is nearby, and expected to return. Kindle on standby for when Economist runs out.

Way back on June 9th I ordered a fancy new umbrella. The vendor created a shipping label that very day, and sent me a tracking number. For reasons (perhaps among them, as they claim on their website, precautions in the warehouse against COVID-19), it was six days before they actually handed the package over to the shipper.

As soon as I’d ordered it, I looked ahead at the weather forecast, wondering if there’d be some rain to use it in, but it looked like a full week of dry weather. Of course, after it took a week to actually ship the package, things had changed. Happily, the package was on-track to arrive Saturday—I’d have my new brolly in hand just hours ahead of forecast thunderstorms!

But then the package followed a mysterious path on it’s way from Wisconsin to Illinois:

In what way is this a sensible?

I mean, I’m willing to cut the vendor some slack for taking six days between sending shipment information and then actually tendering the package. I’m sure precautions against COVID-19 reduce their efficiency in shipping things out of their warehouse. But sending the package from Wisconsin to Illinois via New Jersey and then Missouri? They spent 5 days getting the package to a different adjacent state, to a city only 72 miles closer than where it started!

Now that the package is in the hands of the post office, I figure it will actually get here in a couple of days, just about the time the wet weather ends and it gets sunny and dry for a few days.

This article makes a good point:

“Ultimately, we the public will decide when the economy reopens, not the government.”

If people decide not to fly, not to stay in hotels, not to eat at restaurants, and to wait and see how things work out before making major purchases, it doesn’t matter if the “stay-at-home” orders are lifted or not.

Always true, just now laid bare by the pandemic:

In transit conversations we often talk about meeting the needs of people who depend on transit. This makes transit sound like something we’re doing for them. But in fact, those people are providing services that we all depend on, so by serving those lower income riders, we’re all serving ourselves.

Always nice to see the workers leveraging circumstances to their advantage, as I expect them to do over the next year or two.

emperor Justinian railed against scarce workers who “demand double and triple wages and salaries, in violation of ancient customs” and forbade them “to yield to the detestable passion of avarice” — to charge market wages for their labor…

Boy are these guys in trouble:

Over the past 40 years, schools, particularly less selective ones, have fought ever harder to attract students. The conventional wisdom held that the best way to do so was to upgrade facilities, build new dormitories and student centers, and provide increasingly luxurious amenities. The result has been a flood of debt…

Source: Coronavirus: U.S. Colleges and Universities Reach Breaking Point

Too bad the Fed doesn’t have any epidemiologists. Or virologists working on vaccines.

My brother adds, “They probably don’t even have any mixologists.”

Of course, it is cocktail hour…

Currently reading: How to do Nothing: Resisting the attention economy by Jenny Odell, ISBN: 9781612197494

I observed a year ago that post-crisis bank regulation amounted to the Fed admitting that it was a failure, with banks treating reserves like pre-1913 banks treated gold. So I’m pleased to see that at least some Fed officials understand that this is a problem.

it is worth remembering that a principal reason for the Federal Reserve’s creation was to facilitate the movement of reserves when needed from banks with an excess reserve position to those in need of reserves

Source: Federal Reserve Board – The Economic Outlook, Monetary Policy, and the Demand for Reserves

Struck by Brett Scott’s great line in “The war on cash“:

It’s not a “cashless society” – but a “bankful society,”

I went to follow @Suitpossum, only to find I already do.