All it took to get this badge was making the dog’s long walk of the day a 5 miler, taking her for all her other ordinary walks, the activities of daily living, and then going for a 6-mile run.

All it took to get this badge was making the dog’s long walk of the day a 5 miler, taking her for all her other ordinary walks, the activities of daily living, and then going for a 6-mile run.

As I’ve written before, I have very mixed feelings about the gamification of exercise. Still, the extremes that FitBit goes to are, well, extreme. Such as yesterday, when I took a couple of very long walks with the dog:

Anybody who follows me knows that I’m all about fitness, gamification, and especially the intersection of fitness and gamification. Add to that a bit of program design, and I’m already patient zero for @TheBioneer’s latest video, even before thinking about larping.

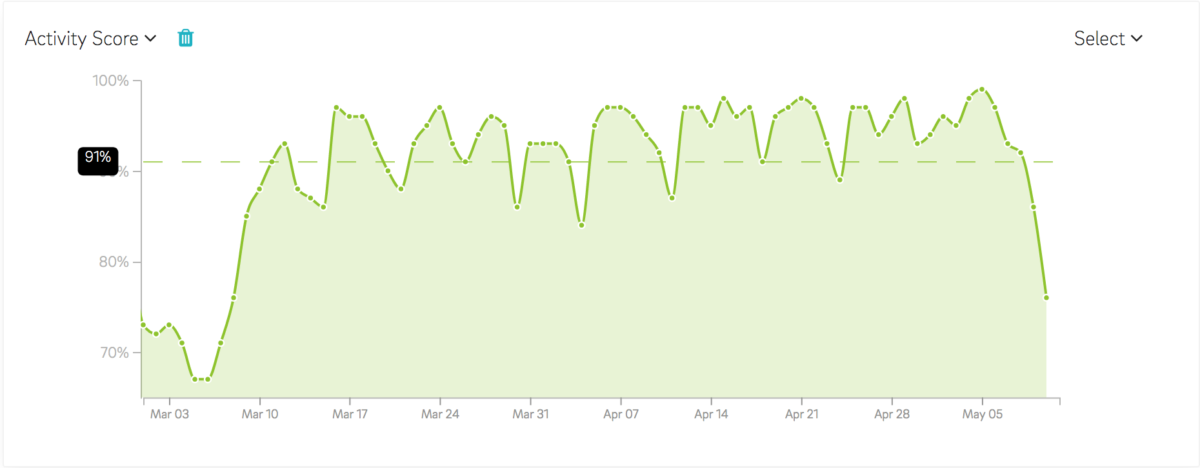

First, let me say that maximizing my Oura ring activity score is, in and of itself, of no value whatsoever—except to the extent that it reflects and reinforces my efforts to get an appropriate level of physical activity.

Happily, I find that getting an appropriate amount of activity generally results in a higher score. So it works at that level, with perhaps a few mismatches between what I think is appropriate and what the Oura software thinks is appropriate, the main one being their idea of what counts as a recovery day.

Periodization of training—getting a mix of training days and recovery days—is a great idea. In fact, the lack of periodization is one of the limitations with Google Fit, whose model is to have a daily activity goal which is a little aggressive—a goal that motivates you to to get out and walk just a little more than you otherwise might. The problem is that a goal that’s even a little bit aggressive is going to be excessive for your recovery days, while still being much less than you probably want for your training days.

This is where the Oura ring software is a big step up from Google Fit. It strongly encourages both training days and recovery days. Unfortunately, its idea of a recovery day seems a bit too strict for me:

For Oura, an easy day means keeping the amount of medium intensity level activity below 200 MET minutes (200-300 kcal/day), and high intensity activity below 100 MET minutes (100-150 kcal/day).

In practice this can mean doing lots of low intensity activities, getting healthy amounts of medium intensity activity (30-60 min), but only a small amount of high intensity activity (below 10 min).

Now, that’s all well and good, except that ordinary walking is a medium intensity activity, and (except when the weather is crappy) it’s a very rare day indeed that I don’t end up walking more than an hour—meaning that I basically never get a recovery day in Oura ring terms.

The result is that whenever the weather is nice my activity score starts dropping, because I’m not getting what my ring thinks is appropriate recovery. Then, when there’s a couple of days of crappy weather and I sit around the house all day, my score will climb (as my recovery time value improves). Then, as soon as the weather gets nice again and I can get out and be active, my activity score can shoot up into the high 90s:

However, I can only get five days of such high levels. Since I need to have at least two recovery days per week, a string of more than five nice days means my recovery suffers once again, turning into lower activity scores.

I haven’t fully characterized the behavior so far, but it seems like the software may well be doing just what the quoted text above says: Getting between 30 and 60 minutes of medium activity makes a day a recovery day, with a hard end to any “recovery” at 61 minutes.

If true, that would probably be the place to make a fix. That is, I’m not trying to suggest that I have any data to show that an average person could walk more than 60 minutes and still recover as well, nor do I have any good metric for identifying some subset of people who can walk more and recover well. But I am pretty sure that the 1 h 3 min of medium activity that I got the day before yesterday is not so much more than the 60 I got yesterday that the former should count as a training day rather than a recovery day.

I gave up multitasking a long time ago. I realized that I’m not good at it, and started paying attention so that I could notice when I was doing it and stop.

As an aside, I should mention that there’s now quite a bit of research to show that nobody is good at multitasking, and that the people who think they’re good at it are even worse than the people who know they’re not.

Even though I’m more efficient doing one thing with complete focus and then going on to the next thing, that practice alone doesn’t solve the underlying problem that tempts people into multitasking: How else can I get everything done?

Half of the answer to that is the drearily obvious, “You can’t. What you can do is get a whole lot done, if you quit frittering away your time on trivial, pointless stuff, and apply your time doing the most important stuff.”

I know some people who are pretty good at that, and they are routinely way more productive than me or most other people.

But there’s more to it than that. Katy Bowman has been talking about one useful practice, suggesting that you “stack your life” by accomplishing multiple goals at once—something that sounds suspiciously like multitasking, but really isn’t.

I’ve actually been thinking about this quite a bit, wanting to articulate the difference for my own sake if no one else’s. My take on it, is that it has to do with what the limiting resource is for each activity.

There are a lot of limiting resources. Your hands are one—they can really only do one thing at a time (although my mom used to read, fan herself, and drink lemonade all at the same time, and felt like she was being very efficient). Location is another—something that can only be done in the kitchen can’t be stacked with an activity that can only be done in the garage or the gym or the grocery store. Other people are another—something that requires the presence of another person can’t be done without him or her. (Though it’s not that simple, as sometimes you can stack up the other people and get multiple things done with multiple people.)

In multitasking, the limiting resource is your attention, and what’s unique about attention is that many activities can be done with partial attention. That experience tempts us into thinking that attention is more divisible than it really is.

Washing dishes only takes partial attention, meaning that you can listen to the radio or a podcast and get full benefit out of both activities.

Driving is a more complex example. We know that driving sometimes requires your full attention. This is why talking on the phone is unsafe to do while driving—talking on the phone requires enough of your attention that doing so reduces your competence at driving as much as getting drunk does. (Talking to someone in the car with you is much less unsafe, because that person can see when the road conditions are such that you need your full attention and shut up. Just listening to something—the radio or a podcast—does not seem to cause the same problem, probably for reasons having to do with deep structures in the brain that prioritize social interactions.)

Even though there are plenty of activities that can be done with partial attention, most important activities require full attention to be done well.

Writing a blog post can be done with partial attention, but when I try to do it while simultaneously listening to a podcast, checking my twitter and facebook feeds, chatting with a friend on-line and another in-person, and answering the occasional email message, I don’t do it as well.

As I’ve worked to apply this lesson—noticing when I’m multitasking and then refocusing on the main thing I’m doing—I’ve learned something else: Many activities that don’t require full attention turn out better when I give it to them anyway.

Beyond that, I feel better when I give my full attention to whatever I’m doing.

It was the meditation practice that I adopted as part of my taiji practice that taught me this. First, it taught me the skill of paying attention, then it taught me that paying attention to what I was doing right now paid dividends, even when all I was doing was sitting or standing.

I’ve noticed it particularly with exercise. I used to distract myself from exercise with music or podcasts or games like Zombies, Run!, because I found exercise to be unpleasant drudgery that I only engaged in to the extent necessary to build and maintain a basic level of fitness. I don’t do that any more. It’s much better when I fully embody my exercise: I enjoy it more, I’m less prone to injury, and the exercise is more effective.

The more I do this—give my full attention to whatever it is I’m doing, whether it seems worthy of full attention or not—the more I find it worthwhile.

Downside: I’m falling behind on my podcast listening, because there are so few things where I feel like partial attention is all they deserve. Maybe I’ll find more, but at the moment I’m just about down to riding on the bus.

So, yes: Stack your life. If you can do one thing with your brain, one thing with your hands, and one thing with your feet all at the same time, go for it. But think twice before dividing your attention. If something is worth doing, it may well be worth your full attention, no matter how hard that makes it to get everything done.

Via an Art of Manliness podcast interview with Steve Kamb, I just learned about his new book Level Up Your Life. The book is just out, so it’s not so surprising that I hadn’t been aware of it before, but I’m a bit surprised that I hadn’t been more aware of the author’s website Nerd Fitness, which has been around for a while.

The site can’t be completely new to me: my browser remembers that I previously visited the definitive guide to parkour for beginners page, but I must have been totally focused on parkour that day, because I didn’t notice that the site is also full of other stuff that is very much my sort of thing: gamifying exercise (and life).

I haven’t read the book, but the interview laid out the case for how gamification can help you succeed, and not just at exercise. Kamb described how to use the motivational tricks of video games—that ones that keep you playing for one more minute, and then one more level, and then one more quest—and apply them to real life. Figure out what you want to do, and then divide those big goals into quests. Just like in a game, design a series of sub-quests, each one designed to give you the skills and experience to accomplish the next sub-quest, until finally you’re ready for the final level, where you face the biggest challenges, and overcome them.

It works great for fitness, where you can set a whole series of fitness goals, but the author was clear that it worked just as well for non-fitness goals. He talked in particular about international travel—that he wanted to do, but found intimidating, and that he approached by designing a series of trips that let him overcome one daunting aspect at a time (distance, foreign language, traveling alone, etc.). He also talked about learning to play a musical instrument, and then leveling up to where he could perform for an audience.

As someone who does just a little gamification of his own life, I got a bunch of useful ideas from the interview.

One I liked was a way to help you divide your attention among the inevitably many high-priority items in your life: the classic comic book trick of a secret identity. By day, a mild-mannered cubicle worker; by night, a secret agent honing his parkour skills for when he’ll need them to complete his mission (and survive the aftermath). Just like any superhero, you need to give both parts of your life the full attention they’re due.

Another was to use a trick nabbed from games for designing rewards for successfully leveling up: Instead of rewarding yourself with a taste of failure (such as rewarding yourself for losing weight with a supersized fast-food meal), do what video games do: give yourself a reward that improves your chance of success with the next quest. If your quest was to learn how to cook, reward yourself at level 5 by buying a really good chef’s knife, and then at level 20 by traveling to France for a workshop at a world-class cooking school. If you pay careful attention to this as you design your series of sub-quests—instead of just making it up as you go along—I can see you drastically increasing your chance of success at many of the harder sub-quests (because you have provided yourself with the right tool), while simultaneously saving a bunch of money.

Another is to gather allies for your quest. It is very hard to succeed in any area of your life unless the people around you are also successes in their lives. There is a certain temptation to be a big fish in a small pond—to gather people around you that you’re superior to—but then you don’t have people you can rely on when you face problems you can’t handle. There is also the temptation to let people who are better than you do for you what you can’t do yourself—but what would their motivation be? Just as in a multi-player video game, in real life you’re better off (and have more fun) if you have a team of people at about your level. If you’re a beginner, you certainly want a few higher-level players to help, and it’s always okay to have a few lower-level players that you can mentor. Ideally—and it often works out this way in practice—everyone will be better than you at some things and not as good at others. Then you can both help one another out; both learn from one another.

Those are just the things I remember from the interview, there’s more to it than that.

It sounds like a great book. I’ll have to get a copy, and I’ll also have to take a closer look at both Nerd Fitness and the book’s companion site Level Up Your Life.

I have mixed feelings about using the motivating power of maintaining a streak.

Lots of people do it. Lots of writers write every day. Lots of runners run every day. There’s probably no virtuous activity out there that doesn’t have someone who has done it every day (or every week, or every year) for decades.

I understand the power. I feel it too, as I’ll describe in just a moment. But I have mixed feelings about it, primarily for two reasons.

First, it tempts people into doing things they shouldn’t just to maintain the streak.

Any runner who has run every day for years has almost certainly gone for a run even though he or she was sick. If it’s just a cold, that’s merely pointless. But going for a run with the flu is life-threatening.

Second, the demotivating power of a broken streak is huge.

For example, I had a streak going in the game Ingress, where there’s a badge for maintaining an unbroken streak of playing every day. I’d gotten my badges for 15-, 30-, and 60-day streaks. When my 180-day badge was due, I found that had apparently missed a day—my streak had ended at 172 days. I immediately abandoned any thought of getting that badge, and quit making any effort to play Ingress on a daily basis. I still play, but my current streak is 4 days.

Because of those issues, I try to be careful about motivating myself by trying to maintain a streak. I still do it though.

I went for a walk yesterday, only because I’m trying to get out for a walk every day this month.

After I hurt my knees in late October, my ability to walk was constrained for several weeks. It was very sad. I missed the last nice days for outdoor exercise, stuck inside resting my knees.

I find it easy to exercise in the summer, and hard in the winter. Every year I imagine that, if I can just keep going through the fall, I’ll preserve the habit and be able to keep going through the winter. It hasn’t worked very well in general, and certainly is out for this year, so I figured I’d do something different: Establish a new habit. I am perfectly capable of just deciding that I’ll get out and exercise in the winter in particular.

So I did decide that. Specifically, I decided that I’d try to meet the goal I’ve established in Google Fit, to get at least 90 minutes of movement every day.

Google Fit’s evaluation is just a bit odd. It’s central metric is minutes, but what it actually counts is steps, and I have no idea exactly how it translates occasional steps into minutes. It works very well when I go for a walk, but when I do taiji, for example, I get essentially no credit for having moved during that hour.

(As an aside, I should mention that I could just manually enter the hour or two I spend doing taiji. I did that for a while, but it isn’t really satisfactory. Among the great thing about Google Fit are that it’s simple and objective—there’s no need to do anything other than just carry my phone all the time, which I do anyway. Manually entering activity misses the whole point.)

Anyway, yesterday was a cold, wet, snowy day. Just the sort of day on which any sensible person would decide to simply stay inside. But I had this unbroken streak going, and a plan to hit 90 minutes of movement each day in December. So, I went out in the cold, wet snow and walked the remaining forty minutes or so to hit the mark.

During the summer, one can just stay in when the weather is bad, and still get plenty of exercise. Do that in the winter, and it’s all too easy to end up spending three months indoors. So, I am using the power of an unbroken streak to prevent that.

Another couple of weeks, and it will be a habit. A couple of weeks after that, and I’ll have met my movement goal for the month of December—and having gotten that far, I expect I’ll be able to move enough in January and February as well.

For now, though, I’ve just checked—and I see that I need another 24 minutes of walking today.

At least it’s not snowing.

There’s a good Oliver Burkeman piece in the Guardian on gamification, or what Jane McGonigal calls living gamefully: using “the same psychological principles, featuring mini-challenges, systems for winning points, completing quests and moving upwards through levels,” to motivate people to do ordinary real-world stuff like exercise or go to work. Burkeman suggests that gamification “reliably divides people into those energized by it and those utterly appalled,” so I wanted to call myself out as an exception, because I’m both.

First of all, I’m totally in the target audience for this sort of thing. I remember seeing this comic in 2006, back when I was still working a regular job, and finding it spoke deeply to me.

I bought both Zombies, Run! and Superhero Workout by Six to Start, two games that gamify exercise. I found myself strongly motivated to get out and run, even in winter cold, by the story in Zombies, Run!

More recently, I’ve observed myself strangely motivated by Google Fit. Even though my goal is self-set, and the reward for achieving it is merely a splash of orange lines and a “bling” sound, I have been known to nip out in the late evening to walk another six minutes just to get my walking time for the day up to my 90-minute goal.

I would pay serious money for a more clever version of Google Fit—one that could count not only time and distance walking, running, and bicycling, but also keep track of my crawling, hanging, climbing, jumping, balancing, throwing & catching, lifting & carrying, swimming & diving, and grappling & striking.

On the other hand, I recognize that this is fundamentally an error—the same error I talked about just a few days ago, when I explained that, although it’s in my nature to want to figure out what I need and make a plan to get it, I recognize that it’s a mistake. It’s a mistake because the “figuring it out” step is both impossible (intractably complex) and unnecessary (get ample natural movement and you’ll be fine).

And yet . . . . And yet, it is a fact that my life does not have enough natural movement in it. Given that I’m not going to become a hunter-gatherer (and would probably starve to death in a few months, if I didn’t die sooner from exposure or an accident), perhaps “living gamefully” is useful as a way to motivate myself and to keep track of the exercise I need to replace the movement I’m not getting.

I read a lot about fitness.

Non-fiction about fitness can be motivating. I find it especially useful to read when I shouldn’t workout due to injury. It lets me maintain momentum through a period when I’d otherwise be idle. I also find fiction about getting in shape to be motivating. (Either one is generally a lot more motivating than most of what passes for fitness motivation. I’d meant to link that to the motivation stream in the “Fitness” community I follow in Google Plus, but decided against it. Too much of the so-called motivation is either demotivating or outright offensive.)

There’s an issue with this source of motivation: both fiction and non-fiction come with a worldview—a model of what fitness is, what it’s for, what behaviors lead to it.

This is noticeable in non-fiction, particularly when the model is weird as to its goals or methods. But it’s especially noticeable in fiction, because then it gets bound up with the goals of the fictional characters. For example, the hero in Greg Rucka’s Critical Space (I’ve mentioned the fitness montage in the middle of that book before, as a good example of the sort of thing I find motivating) is getting in shape to be ready to defend against an assassin.

As long as I’m choosing reasonable behaviors that lead to fitness in a model of my choice, I figure the fact that there’s an action hero doing some of the same stuff is harmless.

Sometimes the fictional character’s worldview resonates with me. For example, one thing Rucka’s hero describes is that learning how to carry himself—learning how to be balanced, centered—teaches him how to see that in other people. My taiji practice has begun to produce the same result in me. I notice when people do or don’t have a good vertical structure, something that I never would have thought to notice before.

Other times the fictional character’s worldview holds nuggets that are genuinely worth picking up. It’s common, for example, for a hero to get better at paying attention to what’s going on—to be more vigilant and watchful. Clearly a useful perspective if you’re living in a thriller or an action-adventure, but probably even if you’re not. Paying attention to what’s going on around you is just good advice. Even if you’re not being targeted by an assassin, being inattentive makes you more vulnerable to everything from muggings to being hit by a car.

Which brings me to the title of this post. As someone who does not live in a thriller or action-adventure, I have the luxury of not paying attention.

As one specific example, when I play Ingress, I pay very close attention indeed—but the focus of my attention is on the fictional augmented reality of the game. Despite its grounding in the actual built environment of public sculpture, the game really distracts me from paying attention to the people who are nearby. I do make a point of being very careful about cars—I don’t cross roads or driveways with my head down at my phone—but I’m much less attentive to people nearby.

While I’m playing Ingress, an assassin would have no trouble getting to within arm’s reach completely unnoticed.

The other augmented reality game I play, Zombies Run!, isn’t as bad, because it doesn’t occupy my eyes. Even so, its fictional world colors my perspective of the real world.

I’m not alone in this. Mur Lafferty describes the immersive power of the game this way:

I was running to avoid a zombie chase . . . and I passed another runner going the opposite way. I nearly yelled that she was running right toward the zombies and she should turn and race away like me. But since I don’t want to be labeled the neighborhood crazy lady, I didn’t do this. I also feel a need, when I pass someone walking, to tell them that they should pick up the pace because of what is behind me . . .

An immersive game is fun. It is a great luxury to feel safe wandering about in public with my attention on a fictional world rather than the real one. I probably indulge myself a bit too much.

In this case, it would probably be wiser to take the advice of my action heroes, and pay attention.