I have spent a lot of time following the latest research on all sorts of interventions to increase lifespan and healthspan. I am now ready to say that virtually all this time has been wasted.

I guess it hasn’t technically been wasted, in that I’ve come to understand the latest research, and that’s of some value. But when it comes to choosing interventions that might help me, it turns out there’s nothing new beyond the obvious healthy lifestyle recommendations of 20 or even 30 years ago.

There are a bunch of chemical interventions that are interesting—they have definitely been shown to increase healthspan and lifespan in animal models, and have had some very promising results in humans as well. However, it is becoming clear that virtually all of them are either exercise mimetics or fasting mimetics—drugs that activate (some of) the metabolic pathways activated by exercise or fasting.

From a public health perspective, perhaps this is of some interest. Given a population of sedentary people with poor diets it’s easy to foresee a mix of these drugs delaying mortality and morbidity—people will live longer, and during their extended lifespan they’ll have less disability, less illness, and require less medical care.

From my perspective though, it’s completely uninteresting. I would much rather just exercise than take a drug that provides a subset of the benefits of exercise. Similarly, I’d much rather just eat good food than take a drug that simulates some of the effects of doing so.

Do you want to live a long, healthy life? Here’s an plan for you:

- Eat a whole-food diet that’s low in sugar and refined carbs. Try to include a couple servings of salmon (or other fatty fish) per week.

- Finish supper at least 3 hours before bedtime, and make sure there’s at least 12 (preferably 13 or 14) hours between the end of supper and the start of breakfast.

- Get at least 2 resistance workouts a week where you exercise your big muscles (glutes, quads, hamstrings, pecs, traps, lats) until they are briefly very tired.

- Get at least 2 endurance workouts a week where you spend an hour or so exercising at a pace that’s a little more intense than a brisk walk.

- Get 1 workout a week where you raise your heart rate to 80% of its maximum for 30 seconds, rest for 30 seconds, and then repeat for a total of 10 rounds.

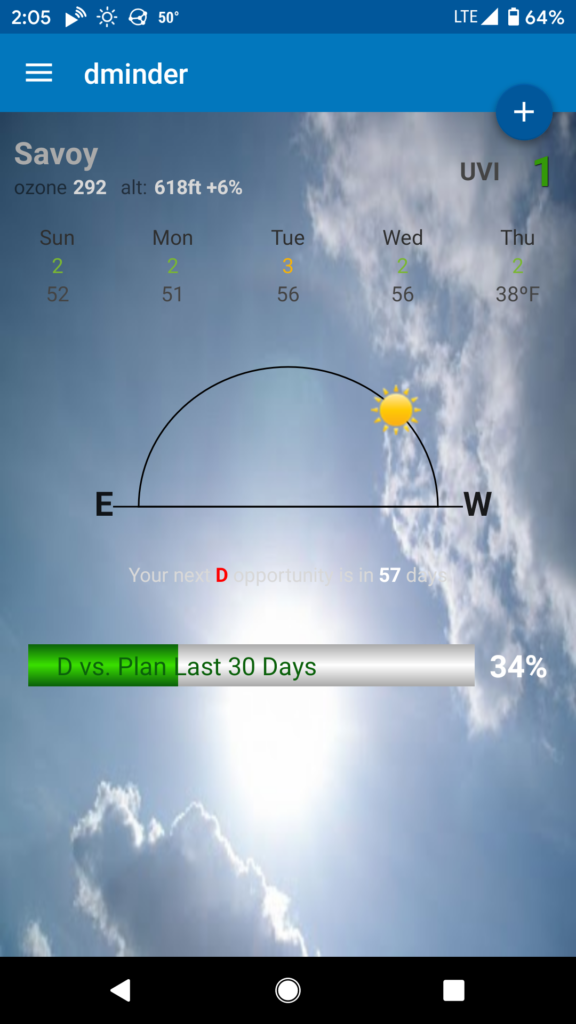

- Spend some time outdoors at least several times a week.

- Sleep until you wake up naturally almost every night.

That’s it. Unless you are sick with a diagnosed condition for which there is treatment, I very much doubt there is anything modern medicine—or even bleeding-edge longevity research—can do for you that you won’t get from this plan.

I’m sure my brother is very amused that it has taken me this long to come to this conclusion.

Probably just another instance of “people who drink moderately have other healthy behaviors as well,” but very much in keeping with my preconceptions:

Probably just another instance of “people who drink moderately have other healthy behaviors as well,” but very much in keeping with my preconceptions: