All it took to get this badge was making the dog’s long walk of the day a 5 miler, taking her for all her other ordinary walks, the activities of daily living, and then going for a 6-mile run.

All it took to get this badge was making the dog’s long walk of the day a 5 miler, taking her for all her other ordinary walks, the activities of daily living, and then going for a 6-mile run.

Badge from my Oura ring today. Photo of me from my HEMA class last night (a guard position called Tag).

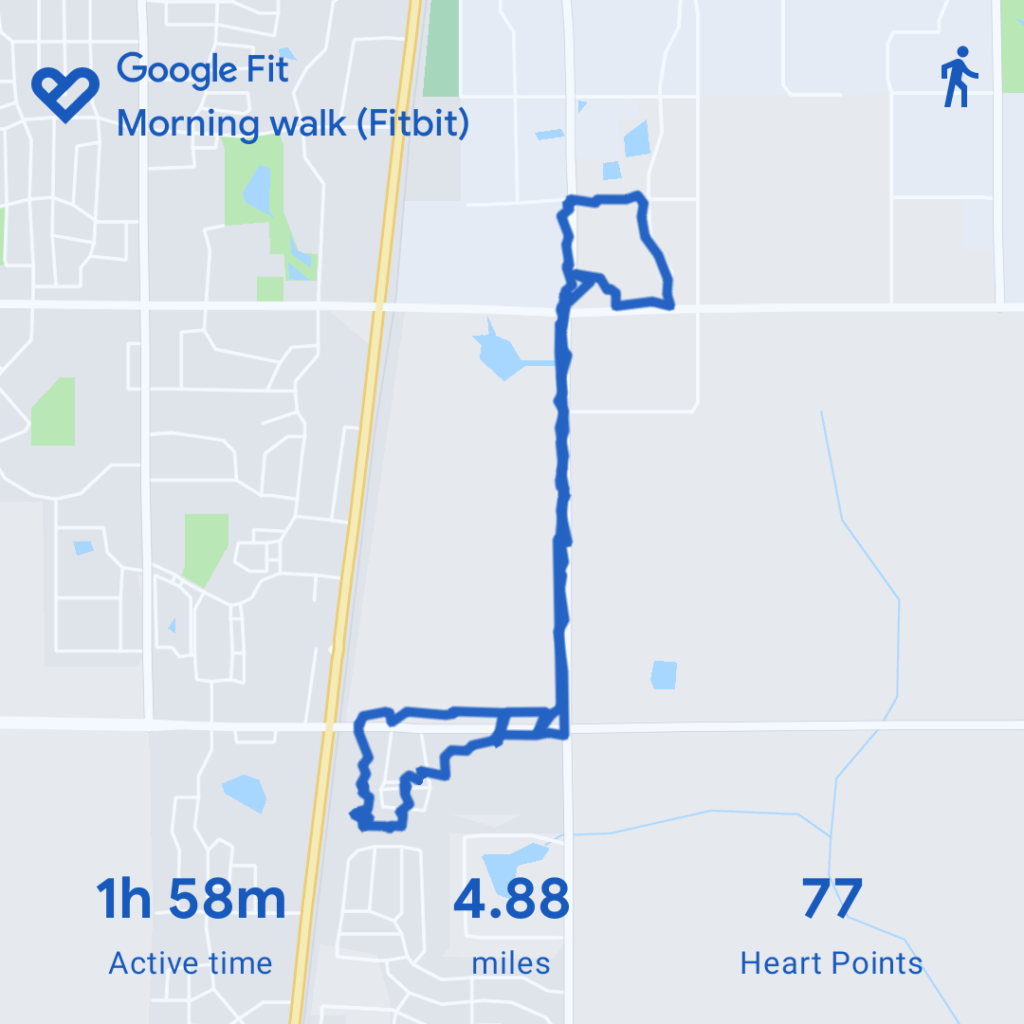

After several days when the weather was too crappy for either me or Ashley to want to take a long walk, it was slightly better today, and I managed to get the pupster out for a pretty long walk.

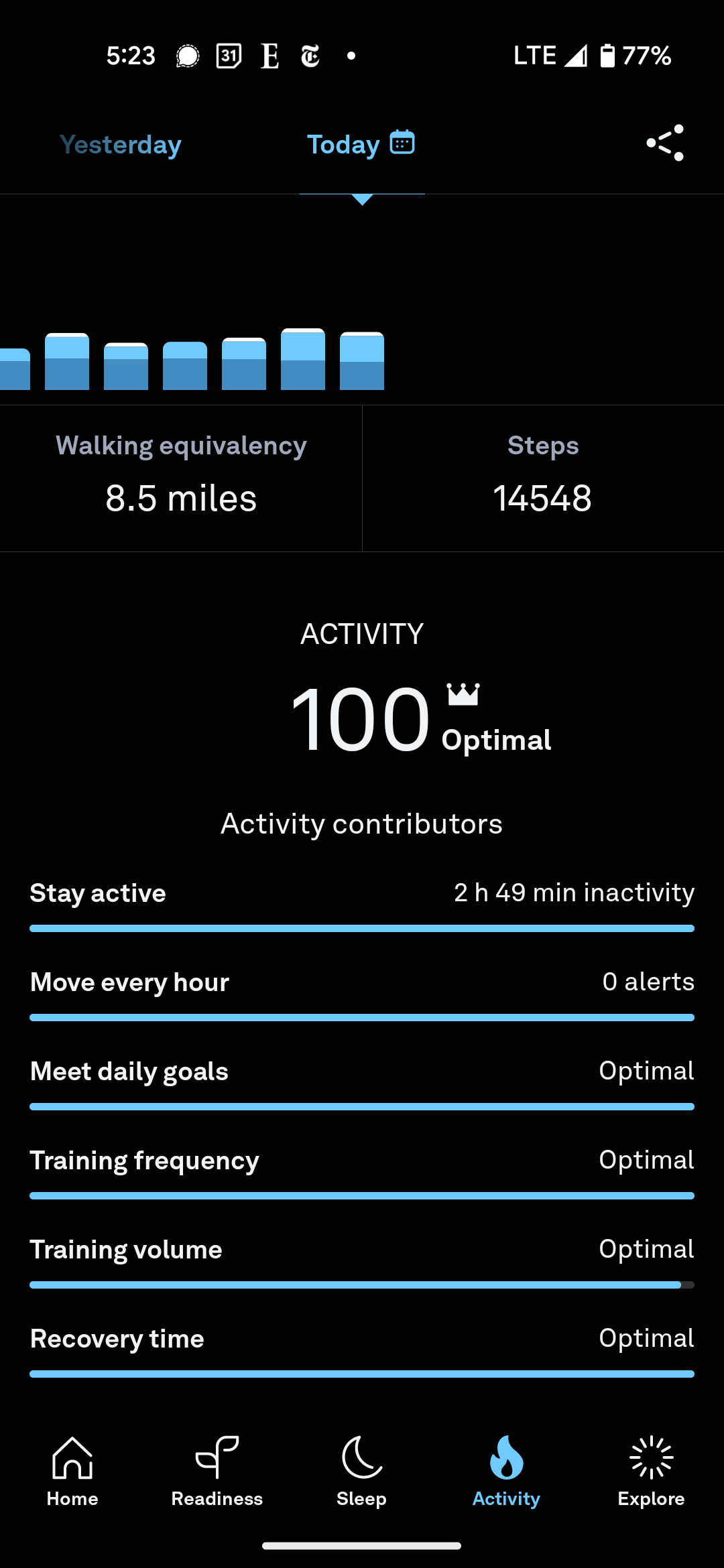

My activity score of 100 due purely to walking the dog. Well, and sleeping better since getting a dog.

I forgot to bring my phone on one of my walks, so those steps only got counted twice and not three times!!! I am bereft.

I get scores in the upper 90s pretty often, but scores of 100 less so. Today I kept my “inactive time” nice and low, which I think is what made the difference.

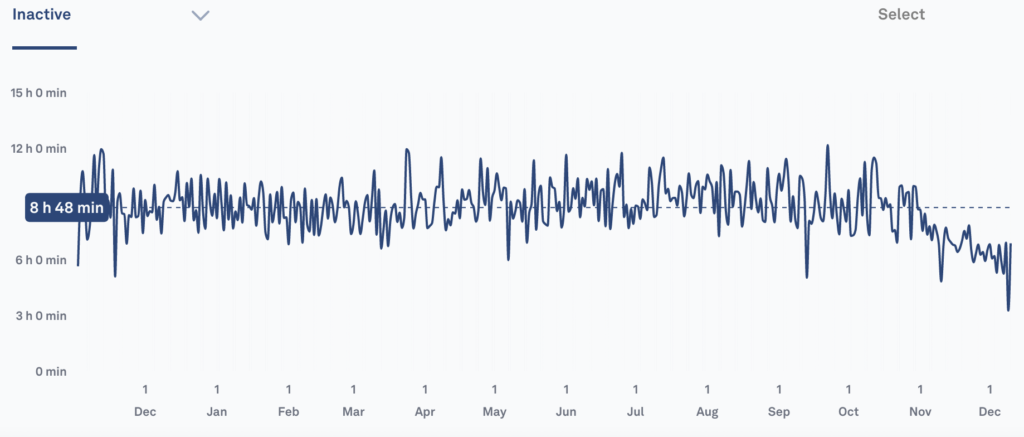

One metric that the Oura ring tracks is inactivity time: basically, the amount of time spent just sitting. It is here that I perhaps see the biggest dog-related change.

I have always spent a lot of time just sitting: I sit to work, I sit to read, I sit to watch TV, I sit to play a video game, I sit to write a blog post, I sit to eat. I sit in the morning while I drink my coffee, and I sit in the evening before getting ready for bed.

The Oura ring folks rather emphasize this particular metric, suggesting that “Keeping your daily inactive time below 8 hours works wonders for your body and mind.” I didn’t doubt this, but I did a pretty poor job of actually doing it. I had the occasional individual day when my inactivity was below 8 hours, but it was usually somewhat over. In fact, my average daily inactive time for the year before we got a dog was 9h 2min.

Since getting the dog, I’ve been way, way more active. I mentioned a few days ago that I was sleeping lot better, and listed a few metrics that had changed that seemed to be related—in particular, walking a lot more, but I hadn’t thought to check how my inactive time had changed, and the results are significant. My average daily inactive time over the 5 weeks since we got the dog has fallen to 6h 38min.

The shift is pretty obvious in a graph of my inactive time starting one year before I got the dog and continuing through yesterday:

The change was dramatic enough that just 5 weeks of post-dog data pulled the overall average down by almost 15 minutes per day. (It’s actually kind of interesting how variable the individual data points are in the first year, and yet how absolutely flat the average is, until Dog Day.)

Well, I have been sitting for rather longer than I probably should to get this post written. I’ll go ahead and post it, and then carry on with the activities of the day.

Since we got Ashley, I have been sleeping better. Remarkably better. It’s kind of amazing.

My Oura ring gives me some data to go on.

The place where it’s very obvious is in deep sleep time. In the month or so before I got the dog, I averaged 57 minutes of deep sleep per night. In the month or so since I got the dog, I’ve averaged 1 hour 23 minutes. Other improvements are significant, but not so impressive in terms of numbers. Total sleep has gone from 7 hours 34 minutes to 7 hours 41 minutes, which is enough to make a difference. Sleep efficiency (the percentage of the time in bed that I’m actually asleep) has gone from 87% to 89%, which doesn’t look so impressive, but also seems to make a difference. I’m also getting up much less often in the night.

Of course, this leaves me with the question of why.

I think partially, it’s just that she sets a great example: She comes to bed when we do, lies down between our feet, goes to sleep, and stays asleep—better than I do, anyway.

The other big change, of course, is that I’m walking way, way more than before.

Again the Oura ring provides some data, with “walking” that has gone from 7.3 miles to 11.2 miles per day. That’s misleading though, because the Oura ring reports a “walking equivalent” number. (Based on, I assume, my heart rate during other activity, such as weight lifting.) The FitBit software on my Pixel Watch gives me actual distance data, and the last half of October I was averaging 5 miles per day, while last week I averaged 7 miles.

After not making a big deal out of my having an Oura ring for 1, 2, or 3 years, Oura has presented me with a fancy graphic to celebrate my having tracked my sleep for 4 years.

I wrote this a while ago, after seeing two articles in two days ragging on fitness tracking devices, and suggesting that they’re bad for you. Both articles warn against outsourcing your intuitive sense of “how you are” to some device. And, sure, I guess you can do that. But if you actually are doing that, I’d suggest that what you have isn’t a harmful device. What you have is a device disorder.

I was going to make an even stronger statement along these lines, comparing a device disorder to an eating disorder. I think the comparison is valid, even though, upon reflection, it weakens my argument. Sure, some people have an eating disorder. But anybody is likely to engage in disordered eating when they eat industrially produced edible food-like substances. Maybe that’s a fair comparison with industrially produced fitness-tracking devices. Unlike with industrial food though, I think the data from fitness trackers can be consumed safely.

“… sometimes I would wake up in the morning and check my app to see how I slept — instead of just taking a moment to notice that I was still tired…”

Source: Opinion | Even the Best Smartwatch Might Be Bad for Your Brain – The New York Times

I get this, because I joke about this myself. My brother will ask how I slept, and I’ll say, “I’m not sure—I haven’t checked with my Oura ring yet.” Or I’ll say something like, “My ring and I agree that I slept well last night!” But I’m just joking. I know how I slept, I know how recovered I am from the recent days’ activities, and how ready I am to take on a physical or mental challenge.

That doesn’t make the data from the Oura ring useless. My intuitive sense of how I am isn’t perfect. Many’s the time I’ve let wishful thinking convince me that I’m ready for a long run or a tough workout not because I really am, but because the weather is especially nice that day and the next few days are forecast to be cold or rainy. Or because I have some free time that day and the next few days are going to be busy. My Oura ring has been a useful counterbalance to that. If I had a hard lifting session yesterday, but I feel great today and my heart rate lowered early last night, maybe I am really ready for a long run today. On the other hand, if my heart rate took the whole night to get down to its minimum, and its minimum was higher than usual, that’s a good sign that I’m not fully recovered, even if I’m feeling pretty good.

If you have an eating disorder, do your best to avoid triggers that lead to disordered eating. Similarly, if you have a device disorder, it makes good sense to avoid using whatever sort of devices lead to disordered behavior. But that doesn’t make the devices bad, any more than eating disorders make food bad. But any particular device might be bad for you, just like any particular food might be bad for you. (And, I admit, industrially produced edible substances are probably bad for everybody.)