“This isn’t what we voted for!” scream a bunch of American racists and fascists who voted for exactly this.

Tag: money

2025-03-21 11:44

“… food delivery giant DoorDash announced a deal Thursday with buy-now, pay-later outfit Klarna, offering hungry consumers “the added convenience of Klarna’s seamlessly integrated, flexible payment options while shopping.”

Source: Almost Daily Grant’s Commentary

Of course. Who doesn’t think it’s a good idea to spread the cost of your lunch over a few weeks or months?

Our new upcoming stagflation

A group of friends and I agreed last week that the most likely result of the most likely policies coming out of this administration is stagflation.

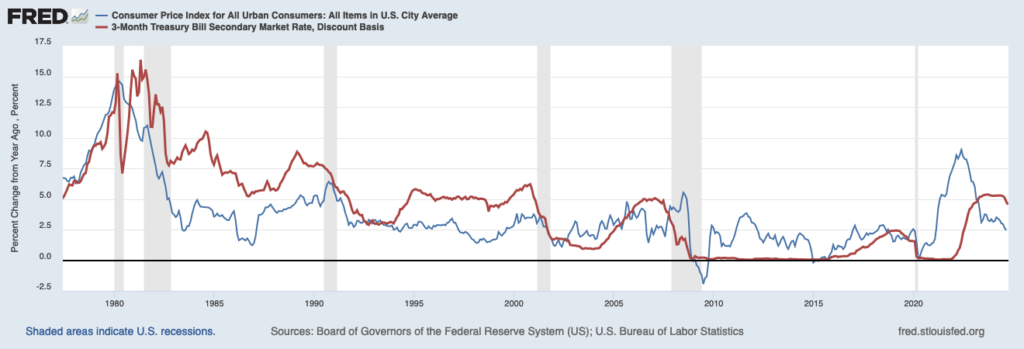

Talking about it reminded me of the Wise Bread post I wrote All about stagflation, so I re-read that. I think has held up pretty well, even though circumstances (financial crisis followed by a pandemic) meant that things didn’t play out as I’d expected. Even so, I think the analysis of how to produce a stagflation is right on: raise interest rates to bring down inflation, but then panic when it’s clear that you’re in danger of producing a recession and cut rates before you’ve gotten inflation under control; repeat until you have high inflation and a recession.

That is, stagflation is usually the result of a timid Fed, that’s afraid to do its job.

The thing is, the policies that I see coming (tariffs and tax cuts) will produce stagflation even if the Fed does a great job. The tariffs directly raise prices, and the tax cuts (through increased deficits) raise interest rates, producing a recession.

In the Wise Bread article I warn that it’s tough to position your investments for stagflation. The reason is that inflation makes the money worth less (helping people with debts, but hurting people with money), while the recession hurts people with debts and people with investments.

Upon reflection though, I don’t think it’s quite that bad. In fact, it’s really just regular good financial advice:

- Avoid debt (you’ll get crushed by a recession faster than you’ll get rescued by inflation).

- To the extent that you have assets, move them into cash (initially you’ll get screwed by inflation, but pretty soon rising interest rates will save you).

- Limit your investments in stocks, and especially limit your investments in your own business (both much too likely to get crushed by recession).

Basically: live within your means and stay liquid.

2025-01-19 07:25

I had one of these accounts whose rate never went up as interest rates rose. I kept it longer than I should have, but I eventually switched banks. (I wasn’t going to switch to their higher-rate “Performance Savings,” because screw that. They can pay a market rate, or they can lose my business.)

[Capital One] operated two separate, nearly identically named account options — 360 Savings and 360 Performance Savings — and forbade its employees to volunteer information about or marketing… the higher-paying one, to existing customers.

Source: NYT

Libertarians, crypto-bros, tech-bros, and incels

Playboy magazine and Helen Gurley Brown. That’s what last week’s New York Times opinion piece, Barstool Conservatism, Revisited (on the weird agglomeration of libertarians, crypto- and tech- bros, and incels who ended up voting with social conservatives) made me think of.

My thoughts draw on a book I read about Hugh Hefner, Playboy, and Helen Gurley Brown. The basic thesis, as I recall it, was that Hefner wanted a society where young men could enjoy an extended youth. The best way to make that work, he thought, was for women to be able to support themselves—so that they’d be willing to sleep with men, rather than feeling that they had to hold out for a man who would marry them.

To that end, Playboy magazine was very active at promoting equal rights for women—so they could earn money, own property, etc. Because only when they were able to support themselves without needing to get married, would they be willing to sleep around. And women willing to sleep around, were what the Playboy demographic wanted.

That social experiment played out pretty much just the way Hefner wanted through most of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. Women could earn enough to afford an apartment, food, clothing, and the other necessities, which meant that they didn’t have to get married just to survive.

However (and this was key, even though I don’t think Hefner really thought about it much) men earned more than women.

The result was perfect for men. They had enough money to buy fancy cars, fancy stereos, fancy watches, expensive liquor—all the sorts of products that advertised in Playboy—with enough left over that they could afford to take women out on nice dates and buy them little gifts. The women earned enough less that, although they could get by, they couldn’t have really nice things, except when men bought them.

Things began to change the 1990s, when women’s incomes grew to the point that they could afford nice things. That produced two changes. First, women that could afford not merely a tiny apartment, but their own house, weren’t so reliant on men to make them comfortable. Second, with so many women taking top jobs, there were fewer top jobs for men. That meant that more and more men found it tough to earn an income that let them improve a woman’s standard of living.

This situation is what has the incels so unhappy. For decades, even after women weren’t legally subservient to men, men generally had enough money that they had something very tangible to offer a woman. Now that’s only true for the top few percent of male wage earners.

Of course, any man with either ambition or good sense could work around this situation. Becoming one of the 1% is hard, but simply having enough ambition to get into, let’s say, the top 50%, means that you have enough of a surplus to be able to raise the standard of living of a woman. And good sense is all it takes to do a bit of an analysis and realize that following the strategies of the pick-up bros isn’t going to lead to what you want nearly as well as coming up with things to offer to women besides cash. (Different things for different women, but: getting fit, wearing nice clothes, learning about the arts or science or history—whatever any particular woman is interested in, paying attention to them when they talk, being supportive of their efforts, are all things that might work.)

But incels as a group don’t seem to want to make even that modicum of an effort. They’d rather blame women.

The other groups I mentioned are broadly similar. Even the rich, successful tech bros are often dysfunctional to the point that they have trouble attracting women. Libertarians are often attracted to the movement specifically because what they yearn for is a world where people have minimal legal protections from the wealthy (and for no good reason, they imagine that they’ll be wealthy enough to take advantage of that). Crypto bros are the same, except they have a specific (rather than vague) notion of where their money is going to come from, even if it’s a fantasy.

So I understand that article. I think that is why all those disparate groups came together, even when their actual interests are pretty disparate.

The big question is, will these groups hang together going forward? Or will the fact that they have nothing much in common except a fantasy of enjoying being on top, lead to infighting and failure?

I’m hoping for failure, but it’s still too soon to say.

2024-12-24 07:18

I keep hearing this stupid ad which, due to an infelicitous pause in the audio, seems to say, “Before you invest carefully, consider the funds objectives, risks, charges and expenses.” I always want to respond, “Before you invest carelessly, don’t bother.”

Inflation and interest rates in 2025 and beyond

Let me start by saying that, judging from his previous term, most of what the incoming president says has no particular bearing on what he’s going to do. But I think a few trends look likely enough that it’s worth thinking about the results on the dollar’s value.

The things I’m thinking of are tariffs and tax cuts, which I expect to lead to higher inflation and larger deficits, both of which will lead to higher interest rates.

Tariffs

The president can impose tariffs on his own, with no need for congressional action. Whether we’ll get the proposed 60% tariffs on Chinese goods, or whether that’s just a bargaining chip, I have no idea. But I think some amount of tariff increase will be imposed, which will feed through directly to higher prices.

That’s not to say that tariffs are necessarily bad (although usually they are). But they do feed through to higher prices.

Tax cuts

Tax cuts need to get through Congress. If the Republicans get the House as well as the Senate, it’s highly likely that legislation will preserve the 2017 tax cuts set to expire next year, and probably some additional tax cuts, such as a much lower rate on corporate income. It’s also possible that we’ll see the proposals to cut tax rates on tip income and on overtime pay enacted, although I doubt it. (The incoming president only cares about his own taxes, not about those of random working-class folks.)

The main thing taxes cuts will do is dramatically increase the deficit. The tariffs will bring in some countervailing revenue, but not nearly enough to fill the gap.

Other things that raise inflation and cut revenue

There are all kinds of other proposals that were bandied about during the campaign, such as deporting millions of immigrants, that raise costs both for the government, leading to higher deficits (the labor and logistics both cost money, and not a little) and for employers (they’re employing the immigrants because their wages are lower), which they will try to offset with higher prices.

What this means for our money

Rising costs will feed directly into higher prices, which is going to look like inflation to the Fed, so I think we can expect short-term interest rates (the ones controlled by the Fed) to get stuck as a higher level than we’d otherwise have seen.

At the same time, lower taxes will mean lower government revenues, leading to larger deficits. For years now, the government has been able to get away with rising deficits, but I doubt if the next administration will have as much success in this area. (Why not deserves a post of its own.)

My expectation is that higher deficits will mean higher long-term interest rates, as Treasury buyers insist on higher rates to reward the risks that they’re taking.

So: Higher short rates and higher long rates, along with higher inflation.

What to do

I had already been expecting inflation rates to stick higher than the market has been expecting, so I’d been looking at investing in TIPS (treasury securities whose value is adjusted for inflation). I’m still planning on doing so, but not with as much money as I’d been thinking of, for two reasons.

First, I’d been assuming that money market rates would come down, as the Fed lowered short-term rates. Now that I think short-term rates won’t come down as much or as fast, I’m thinking I can just keep more money in cash, and still earn a reasonable return.

Second, I’d been assuming that treasury securities would definitely pay out—the U.S. has been good for its debts since Alexander Hamilton was the Treasury Secretary. But the incoming president has very odd ideas about bankruptcy. As near as I can tell, he figures the smart move is to borrow as much as possible, and then declare bankruptcy, and then do it again. It worked for him, over and over again. I’m betting that Congress won’t go along with making the United States do the same, but I’m not sure of it.

Of course, if the United States does do that, the whole economy will go down, and my TIPS not getting paid will be the least of my problems.

Undoing inflation is possible. It’s just bad.

Looked at properly, inflation is the money getting less valuable, which shows up as rising prices. It’s opposite, deflation, is the money getting more valuable, leading to falling prices. Something that used to be very obvious, but has perhaps become less so, is that inflation sucks if you have money, whereas deflation sucks if you owe money.

TL;DR version: You can reverse inflation, as long as you’re willing to grind into the dust everyone who owes money, making them work more and more, to earn less and less, to pay back debts that get higher and higher (because the dollars it takes to pay them off are getting more and more valuable). Society has done that many times in the past. Sometimes it works out okay; other times it produces terrible impoverishment of ordinary people, leading to social unrest.

The rest of this post looks at this in a bit more detail. I was prompted to write it because recent polls have suggested that young folks—Millennials and Gen-Z—continue to be unhappy about inflation, even though the inflation rate is down a lot. When you talk to these people, it turns out what they’re unhappy about is not inflation but rather prices: They remember what things used to cost, and they cost more than that now, which they find annoying, even if the price has largely quit going up. (And of course prices change all the time, so some prices are always going up.)

Older folk—people who lived through the inflation of the late 1970s and early 1980s—have a different perspective on that, partially because their parents and grandparents lived through the Great Depression.

Basically, they remember what happens when you try to push prices back down to what they were before a period of inflation.

There’s a sense among the “hard money” types that inflation is impossible when the currency is backed by gold, but this is false. There is often inflation under a gold standard, but it (often) ended up getting undone, meaning that looked at from the perspective of a century, it looks like there wasn’t much inflation. And indeed there wasn’t much inflation on average.

This was especially true during the heyday of the gold standard, roughly the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1816 the pound sterling was defined as 113 grains of pure gold, where it remained until 1931. (Before that it was defined as 5,400 grains of silver—about a pound of silver, hence the name a pound sterling—but in terms of value it was a similar amount of purchasing power.)

A big part of the reason that people remember the gold standard fondly is that it worked pretty well, especially for people who had money. With stable prices, it was even possible to value land not at a market price (because who would sell land?) but at the income that land would produce—an income that would remain stable for generations at a time.

However, as I said, there was still inflation. Inflation came from many sources, but two important ones: new discoveries of gold, and war. When the quantity of gold increased—as during the 1840s and 1850s when large amounts of gold were found in California and Australia—the rising quantity of gold (i.e. money) would produce inflation just like rising quantities of money produce inflation now. The other common source of inflation was war, because paying for a big war without inflation is almost impossible.

For example, there was a big inflation in the U.S. during the Civil War, when the Federal Government printed “greenbacks” to pay for the costs of the war. (The Confederates did the same, but as they lost the war their Confederate dollars ended up being worthless.) Dollars, on the other hand, were gradually revalued, with greenbacks gradually being withdrawn from circulation producing a grinding deflation that went on for more than a decade.

Like always in economics, there were other things going on at the same time. Industrialization was going on at the same time, meaning that things produced by industrial firms were getting cheaper, leading to deflation, while gold discoveries were leading to an increase in the supply of gold (= money) leading to inflation.

On balance there was deflation, meaning that people who had money were getting richer, while people who owed money were getting poorer. As long as that happens only in a small way, and as long as people sense that it’s “fair”—that nobody is cheating the system to take unfair advantage—it’s kinda nice. If you don’t owe money (and most people didn’t, because there were no credit cards, and virtually no student loans), then whatever meager savings you had got gradually more and more valuable. At the same time, wages tended not to drop (for the same reasons that wages tend not to drop these days as well), so somebody with a job ended up gradually better and better off.

Of course rich people got vastly more well off, so they loved it. The main people who hated it were farmers and small businessmen, because they generally needed to borrow money (to buy seed or raw materials), so they were constantly screwed by the fact that the money they had to pay back was worth more than the money they’d borrowed.

I started this post meaning to suggest that “kids these days” just didn’t understand the dynamics of deflation, But upon reflection, I think there’s another layer to it. Kids these days (as opposed to the Gen-X kids who trusted their parents and guidance counselors, and borrowed as much money as necessary to go to the best school they could get into) don’t owe so much money, so they’re not in the position of being utterly screwed by deflation. Many of them may be in the position of ordinary people in the great post-Civil War deflation, who ended up doing pretty well, with their wages or salary rising in value, while industrialization and globalization helps hold down prices.

The fact is, though, that deflation can absolutely destroy a generation of ordinary people. After WW I, for example, Britain, having funded the war through inflation, decided to return to the pre-war gold parity, which required a grinding deflation that lasted until 1929—great for people with money, bad for people without, devastating for people with debts. France decided instead to revalue, punishing people with money, coddling people with debts (which has its own downsides in terms of social disruption). German, the loser of WW I, saddled with debts denominated in gold, made a valiant effort to pay them back, giving up and starting WW II only when that proved utterly impossible.

The lesson of that period, understood by pretty much everybody from the 1940s through the 2000s, was that the best thing to do after a period of inflation was to bring the inflation rate back down near zero, but accept the price increases that had already happened. (If the inflation rate is brought back down to, let’s say, 2%, prices will be generally stable. The slight remaining inflation will be barely noticeable, hidden amidst the ordinary rise and fall of prices due to changes in fashions, technological improvements in the means of production, depletion of resources, etc.)

It’s very interesting to see young folks returning to the instincts of the 18th and 19th century, thinking the prices should go back to what they were before the inflation. It goes very much against what I learned as an economics student, but who can say that what I learned was right and that their instincts are wrong?

Seems like a situation of “time will tell.”

Sources:

2023-12-31 10:23

My ambition has long been to be a young man of independent means. I achieved the “independent means” part some years ago, but I don’t seem to be making much progress toward being a young man.

Still working on it!

Roll your own Cash Management Account

Back in the late 1970s, Merrill Lynch, and then several competitors, created what became known as a Cash Management Account. I really wanted one.

Basically, a Cash Management Account was a brokerage account wrapped around a money market fund and an associated credit card.

It was really aimed at high-value customers. The sort who might make discretionary purchases in the $10,000 range. The sort who wouldn’t want to have multiple tens of thousands of dollars sitting around in cash just in case a few of those purchases might end up being made in the same month. For those customers, a key feature was that the brokerage account was a margin account.

You had an American Express card tied to your account. You could charge whatever you wanted, just like on any other AmEx card. At the end of the month the account would automatically pay the balance on the card. You also had a checkbook that you could use to pay your bills. If either kind of transaction drained the cash out of your account, you’d automatically get a margin loan against your investments. Margin loans were at a preferred rate (because they were secured).

At your own convenience, informed by knowing when more cash would be flowing into your account (dividends on your stocks, interest on your bonds, transfers from the trust your daddy set up for you), you could either let the margin loan be paid off by incoming cash, or else decide to sell some asset or another.

For someone with liquid assets in, let’s say, the million dollar range, it was really very convenient. For someone with much less than that it was less useful, but to keep out the riffraff (people like me), they required a minimum initial investment of $20,000.

By the time I had the money to buy into an account like that, it’s advantages had pretty much been rendered moot by modernization in the financial industry. Now you can roll your own cash management account easily enough.

Here’s what I do:

- Have a local bank account for checking and a debit/ATM card. (Nowadays it wouldn’t have to be local, but I like having access to a local branch for teller services, a safety deposit box, etc.)

- Have an internet bank for a high-yield savings account.

- Have a brokerage account for investments.

- Have a credit card.

I have these accounts connected so that I can transfer money between them via the Automated Clearing House (ACH).

I make my local bank the center of everything: All deposits and all payments flow into and out of that checking account. Any time that adds up to surplus money, I transfer the funds to my internet bank to pick up the extra yield, or else to my brokerage account to be invested.

It’s basically exactly like a cash management account, except that I don’t have paying the credit card automated. (Actually, since I originally drafted this post, I’ve gone ahead and automated paying my credit cards. We went on vacation back in July and August, and were going to be out of town right when the bills could be expected, and not back home until after they needed to be paid. So, now almost all of my bills, finally, are paid automatically. I now live in, I don’t know, 2005 or thereabouts.) Oh, also: my brokerage account isn’t a margin account. (It could be, but the whole preferential rate structure for margin loans faded away some years ago, so there’s no point.)

If there’s something about a formal Cash Management account appeals to you, pretty much any bank, brokerage firm, or mutual fund company offers them now, often with no minimum investment. But there’s really no point.

Currently the ACH takes 2–3 days to move money, but the infrastructure for same-day payments (called FedNow) is now in place. Soon enough a few banks and brokerage firms will make it available to customers to distinguish themselves, and either the others will quickly fall in line, or I’ll move my money to the more enlightened institutions.