Struck by Brett Scott’s great line in “The war on cash“:

It’s not a “cashless society” – but a “bankful society,”

I went to follow @Suitpossum, only to find I already do.

Struck by Brett Scott’s great line in “The war on cash“:

It’s not a “cashless society” – but a “bankful society,”

I went to follow @Suitpossum, only to find I already do.

I have always been an optimizer. I spend way, way too much time, energy, and attention optimizing things. Which is, you know, fine, even though my net benefit is small or zero, largely because I don’t focus my optimization efforts in places where I get the biggest payoff. (I’d say that I don’t optimize my optimization efforts, but I don’t want to tempt my brain into trying to do that. It would not end well.)

One place where my optimization efforts did end well has been in optimizing things for life under late-stage capitalism.

I was helped by a couple of lucky coincidences and a bit of lucky timing.

Purely because I enjoyed doing software, I became a software engineer at the dawn of the personal computer era, which gave me a chance to earn a good salary straight out of college, a salary that grew faster than my expenses for most of the next 25 years.

Whether because of my upbringing or my genes (my grandfather was a banker), I liked thinking about and playing with money, which meant that I was doing my best to save and invest during a period when ordinary people could easily earn outsized investment returns.

It worked out very well for me. I’m as well positioned as anyone who isn’t in the 1% to do okay in late-stage capitalism. (Frankly, better positioned than a lot of the 1%, who find it easy to imagine that they deserve the lifestyles of the 0.1%, and if they live like they imagine they should will quickly ruin their lives.)

This whole post was prompted by a great article that looks mainly at the efforts women make to optimize themselves under the overlapping constraints of health, fitness, appearance, and financial success in the modern economy. Highly recommended—insightful and daunting, but also funny:

It’s very easy, under conditions of artificial but continually escalating obligation, to find yourself organizing your life around practices you find ridiculous and possibly indefensible…. But today, in an economy defined by precarity, more of what was merely stupid and adaptive has turned stupid and compulsory.

Athleisure, barre and kale: the tyranny of the ideal woman by Jia Tolentino

One focus of that article is on “fitness.” I put fitness in quotes because of the way, especially for women, so much of fitness is actually about appearance. Perhaps because I’m not a woman—also perhaps because I’m already married, and because I’m older—my own perspective on fitness has gotten very literal: I want my body to be fit for purpose—fit for a set of purposes which I have chosen. I want to be able to do certain things because I have found the capability to be useful. (I also want to be able to do certain things that I can’t do, because I imagine that the capability would be useful, and much of the exercise I do now is intended to achieve those capabilities.)

In a sense, optimizing for fitness is really neither here nor there as far as optimizing for late-stage capitalism, which is mostly about money. And yet, really it is. My fitness suffered during the period I was working a regular job. Getting fit and staying fit takes time. To a modest extent, you can substitute money for time—you can pay up for the fancy gym where the equipment you want to use is more available, or take a job that doesn’t pay as much but allows you to squeeze in a midday run. But now we’re right where we started: optimizing for life in late-stage capitalism.

I should say that I’m delighted with how well my life has turned out. If I’d had any idea how little I could spend and still have everything I really want, or how early I’d have saved up enough money to support that modest lifestyle, perhaps I could have avoided a lot of anxiety and unhappiness along the way. But who among us has such luck? And more to the point, maybe some of that anxiety and unhappiness were crucial to my making the choices I did that got me to where I am.

I worry just a bit about my irresistible impulse to optimize, but like everything else about me, it got me to where I am. And, as I say, I’m delighted to be here.

If you refinanced your mortgage 8 or 10 years ago there’s probably no reason to do it again. (Maybe your mortgage is almost paid off!) But mortgage rates are setting new generational lows and if you have any substantial balance left it might be worth refinancing.

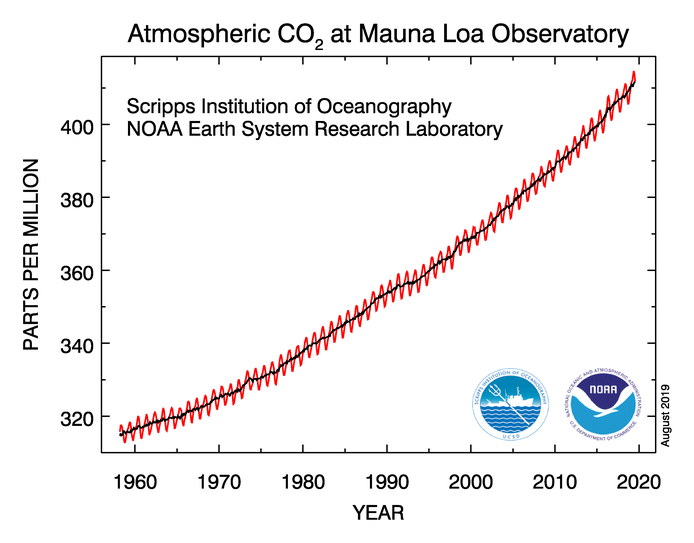

Interesting to me that the Great Recession doesn’t even show up as a blip on this graph.

With no card number, CVV security code, expiration date or signature on the card, Apple Card is more secure than any other physical credit card.

Source: Apple Card launches today for all US customers – Apple

While @jackieLbrewer was working at the bakery there was a cash register glitch. For several days they took credit card payments on paper, writing the number down by hand, and then entering them manually at the end of the day.

Those customers would have been totally secure from being able to buy bread.

Clearly I’m not going to spend $1000 for a jacket like this, but I’d sure like one: https://www.vollebak.com/product/black-squid-jacket/

Often—I’d say usually—when I craft something to post to social media I end up disappointed eventually. In particular, when I want to refer back to it and find that it’s lost in the depths of Facebook or twitter and I can’t find it, or can’t refer to it in the way I want to.

I think I’ve got this problem solved now, via micro.blog, which is social media done correctly.

Use micro.blog like this: Have your own blog that generates an RSS feed. Sign up for a micro.blog, and configure it to watch that feed. It will build a twitter-like timeline out of your blog posts. There’s a clever detail about how it does so: Your regular posts will just be posted with your post title and a link. But your short, status posts—your tweet-like posts—show up with the full content instead of just a title and a link. (You signal the difference to micro.blog by omitting a title on your status posts.)

I set up a micro.blog a couple of years ago (I was a backer on Kickstarter), and was very pleased with how it all worked, with the sole problem being that nobody reads my micro.blog feed. My frustration with that, however, has finally prompted me to do something that I’m always loath to do: Spend money.

I signed up to spend $2 a month to have micro.blog forward my feed on to twitter (and, of course, to support micro.blog). A link to this post will show up with the post title. My status posts are showing up as tweets, just like they’re supposed to.

Going forward I’ll still post to twitter, but generally just replies and retweets. With those exceptions, my plan is to publish all my content here and let micro.blog handle the rest.

Does money come with new-agey energy flows or emotions attached? For most of my life, I’d have said no (or more likely just rolled my eyes at the question). As you might expect from an economics major, I bought into a free-market model of how money worked.

Experiences over the course of my career, gradually convinced me that those ideas were . . . Well, not wrong exactly, but incomplete. I came to understand that money isn’t the kind of neutral object that it is in economic theory.

Ken Honda’s new book will let you skip over the 25 years of first-hand experience it took me to figure this out.

If you think money is a neutral, transactional artifact, then it just makes sense to earn as much as you can in the easiest ways possible. Because I was a software engineer whose career started in the early 1980s, it was pretty easy to find a job that paid well, and salaries grew rapidly, so I was doing just fine as an employee. There are certain things that come along with being an employee, the main one being that you’re supposed to do what your boss tells you to do.

I was okay with that. More okay than a lot of my coworkers, who objected when the boss wanted them to do something stupid or pointless.

My own attitude was always, “Yes, attending this pointless training class is a waste of time that I could be spending making our products better. But it’s easier than doing my regular work, and if my boss is willing to pay me a software engineer’s salary to do something easier than write software, I’m fine with that.”

The idea that I was fine with that turned out to be wrong. In fact, putting time and effort into doing the wrong thing is a soul-destroying activity. Getting paid a bunch of money for it doesn’t help. That money is, in Ken Honda’s terms, Unhappy Money.

Money that flows into (or out of) your life in a positive way is Happy Money—money that you receive (or give) as a gift, money that you earn by doing something useful (or spend to get something that you want or need). Unhappy Money is money lost or gained by theft or deceit, paid grudgingly by someone who feels cheated or taken advantage of—or, as in my own case, paid willingly, but paid to someone who doesn’t think what he’s doing to earn it is worth doing.

Honda’s thesis is that if you adjust your life around this idea—so that your own money flows are all Happy Money (and that you refrain from receiving or spending Unhappy Money)—your life will improve. My experience is that this is true.

If that insight is the key to the book, probably next most important is understanding that “There’s no peace to be found in always wanting more,” which is one of the points I tried to make when I was writing for Wise Bread.

To be honest, probably one reason I like the book so much is that a lot of the practical advice sounds a lot like what I talked about for years at Wise Bread. (For example that the strategy of just saving more quickly reaches limits in terms of its utility for making your family more secure.)

Much of the book is on the details of how to shift all aspects of your financial life toward Happy Money. There’s a long discourse on what he calls your “money blueprint”: The attitudes and practices passed down from parent to child (or rejections of those attitudes and practices), people’s basic personalities, and simple ignorance about how money works. A crappy money blueprint will predictably lead to people into cycles of Unhappy Money flows.

I’ve been interested in money for a long time, at least since sixth grade. Between studying economics in college, and embarking on an enduring interest in investing, I’m sure I’ve read hundreds of books on money. Among them, Happy Money: The Japanese Art of Making Peace with Your Money stands out.

Why has the Fed been able to produce asset inflation but no price inflation for past 10 years? My guess: lack of union power and globalization are blunting transmission into wages and prices. But I don’t see an easy way to test that hypothesis.

In a recent speech, Fed chair Jerome Powell talked about “balance sheet normalization” in terms that strike me as essentially admitting that the Fed is a failure as a central bank.

Here’s the quote:

The crisis revealed that banks, especially the largest and most complex, faced much more liquidity risk than had previously been thought. Because of both new liquidity regulations and improved management, banks now hold much higher levels of high-quality liquid assets than before the crisis. Many banks choose to hold reserves as an important part of their strong liquidity positions.

Source: Federal Reserve Board – Monetary Policy: Normalization and the Road Ahead

Powell seems to be suggesting that banks have chosen to treat reserves in the same way a gold-standard bank treated specie: as cash on hand to meet demands from depositors who want their money back.

I call this a failure because a big part of the reason behind the creation of the Federal Reserve was that this system—where every bank held some gold—was clearly inadequate. Commentators at the time likened it to a fire protection district which, instead of having a fire engine, required every household to have one bucket of water on hand.

By having a large common stockpile of gold at the Federal Reserve, a loss of confidence in any one bank could be easily handled. Faced with a bank run, a solvent but illiquid bank would bring some assets (loans, bonds, bills, etc.) to the discount window and receive enough gold to handle redemption requests.

Powell is saying that banks seem to have decided that they can’t count on the Fed to discount their illiquid assets—a basic function of a central bank. Instead they’re choosing to stockpile large quantities of reserves exactly the way nervous banks stockpiled gold reserves in the pre-Fed days.

I’m sure this is based on the experience of the financial crisis, where many banks held a bare minimum of reserves and safe assets, choosing instead to invest the maximum amount in complex derivative instruments, which were highly profitable until they suddenly became worthless (or at least of dubious value).

But that just means that this is a double failure by the Fed:

By paying interest on these reserves, the Fed is enabling this behavior—solving the old problem that “gold in the vault pays no return.” But banks should be in the business of facilitating commerce in the economy, not the business of using their depositor’s money to score some free cash from the Fed.

I completely understand the Fed not wanting to again put itself in the position of having to decide what discount rate is the right one to apply to 3rd tranche mortgage-backed subprime paper. But a strategy of “just hold more reserves” is a pretty poor solution to the problem, for exactly the same reason that “just hold more gold” was a poor solution in the pre-Fed days.