Something about seasonal affect disorder makes it really hard for me to resist carbs.

Tag: SAD

Winter running, maybe

I have never been a winter runner. Most years I start running in the spring, ramp up the length of my long runs during the summer, make a plan to keep running through the fall, and then abandon it at the first sign of cold.

I’d like to run over the winter. Exercise helps as much as anything else I’ve tried to stave off SAD. Besides that, there are any number of spring running events that I’d enjoy participating in that I can never do because I’m not in shape until later in the year.

And so, demonstrating my unwillingness to learn from experience, I’m trying yet again to run over the winter.

To help get myself started, I’ve embarked on a consumer binge. First I bought a high-viz hat. (I already had the high-viz running vest and the red buff with reflecty stripes.)

The hat got me out for a run or two.

Another garment that I didn’t really have was running tights. Having a pair of running tights, I figured, would eliminate one more excuse for skipping a run in the cold. Plus I was able to find a pair marked down from $80 to $20.

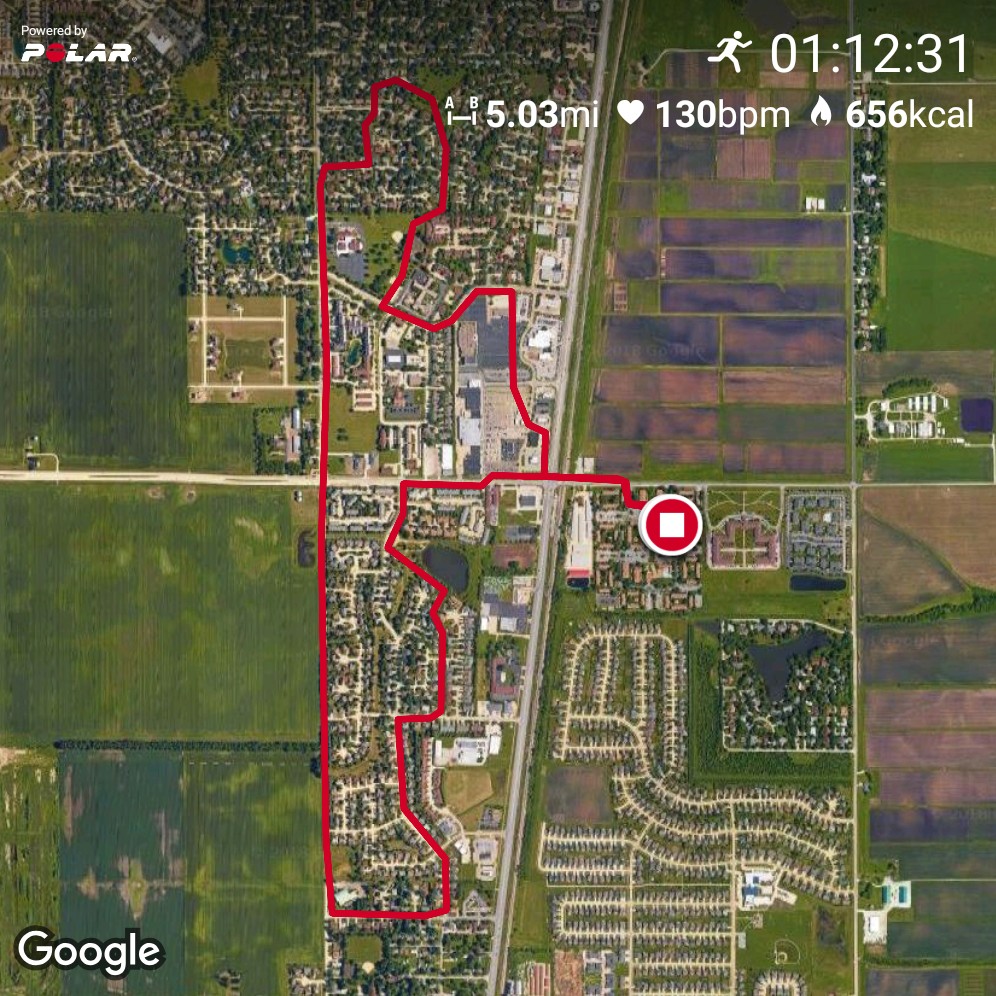

I wore the tights for a 5-mile Thanksgiving Day run. (See map at top.) That’s my longest run in a couple of years, and I felt great right along—no sore ankles, and no sore knees (the places that tend to hurt when I push the distance up too fast).

I did wake up this morning with sore feet—classic plantar fasciitis pain. My feet only hurt for a few minutes in the morning, which is typical with minor plantar fasciitis. I expect it will resolve itself in just a day or two, but even if it does, it’s a pretty strong indication that 5 miles is as far as I should run for a while. (I’d had no foot pain after my previous long run of 4 miles.)

To give my sore feet a break I didn’t run today, opting instead for a 3.2-mile hike at Homer Lake. The trails there are pretty flat and level, but there are some places with lots of tree roots right at the surface, which make for a nice complex surface to walk over, giving one a chance to mobilize the foot joints, highly beneficial for preventing plantar fasciitis.

I’ll post further winter running updates, if I manage to get the habit established this year.

At 5:30 AM

At 5:30 AM, as Jackie heads to work, the sun has not yet risen. It won’t rise until 5:39 today. Worse, the encroaching darkness is speeding up: It won’t rise until 5:45 a week from today.

Exercising in the heat

I have always enjoyed exercising in the heat. In this I seem to be different from most people.

I originally took note of this fondness back in the early 1980s when I was living in Ft. Lauderdale. A ritzy local tennis club—way too expensive for me—offered summer memberships for just $100. I just got access to the outdoor courts and not to the indoor amenities, but all I wanted was a place where I could reserve a court and know that it would be available when I met someone there. The only downside was that you were playing tennis outdoors, in the summer, in Ft. Lauderdale. And it turned out I was okay with that.

I’m pretty careful not to be stupid about it. (And successfully so, it seems—I’ve never gotten heat exhaustion or heat stroke.) If I start feeling tired, thirsty, or overheated, I slow down, move to the shade, and drink some cold water.

Over the years I’ve had a variety of theories about why I didn’t mind exercising in the heat when other people hate it so much. I like to imagine that I’m just better at tolerating the heat than the average person: Everyone slows down in the heat, but maybe I slow down slightly less; at some high temperature, maybe I’d become competitive! More likely, since I’m not competitive I’m not making unfavorable comparisons between my speed in the heat versus my speed in cool weather, so the fact that I slow down doesn’t make me unhappy.

Recent research has given me a new, much more likely reason why I like exercising in the heat. On Rhonda Patrick’s Found My Fitness podcast, I heard an interview with Dr. Charles Raison, in which he described the results of a study suggesting that Whole-Body Hyperthermia was an effective treatment for depression. The experiment used infrared lights to heat people up to a core body temperature of 38.5℃ (101.3℉), but Raison is convinced that there is nothing special about the device used, and that a sauna, hot spring, sweat lodge, hot yoga—or just exercising in the heat—would have the same antidepressant effect.

Dr. Raison is studying further to try to elucidate the mechanism by which hyperthermia boosts mood in depressed people. (It seems to reduce inflammation, perhaps by boosting IL-6 which activates IL-10. Heat Shock Proteins might also be involved, since they do all sorts of things.)

I have always been inclined to blame a lack of daylight for the seasonal depression that I’m prone to suffer from during the winter—both too short of a photo-period (which I address with a HappyLight™) and too little vitamin D (which I address with vitamin D supplements), but it now occurs to me that a lack of opportunity to exercise in the heat (and thereby raise my core body temperature high enough to trigger whatever it is that reduces depression) may be an independent factor.

It seems very likely that, just like my desire to spend time outdoors in daylight is probably self-medicating to boost my vitamin D and regulate my circadian rhythm, my desire to exercise in the heat is probably self-medicating to boost my mood.

I hesitate to rejoin a fitness center just to get access to a sauna, but I’ll have to investigate options for access to winter whole-body hyperthermia.

Getting my mind right with the cold

After posting a couple of weeks ago about how I was having trouble adjusting to the cold and dark, I got a comment from Srikanth Perinkulam suggesting that I take a look at What Doesn’t Kill Us by Scott Carney, which I have now done.

The book grabbed me right from the start. The forward by Wim Hof is delightful. The preface sets the stage for the climactic event. In the introduction the author suggests that his spirit animal is a jellyfish—a comforting thought for someone like me whose totemic animal is the sloth.

Because the first few pages were so interesting, I suggested that my brother use Amazon’s “look inside” feature to read them, but he was unwilling to do so—pretending to be daunted by the fact that the “look inside” feature depends on scripts he had turned off in his web browser. He also declared the book to be “pseudoscientific drivel.” (A comment that must have been—since he wouldn’t read even a few pages—based entirely on the subtitle: How Freezing Water, Extreme Altitude, and Environmental Conditioning Will Renew Our Lost Evolutionary Strength.)

Of course it’s not a scientific book, but rather a journalistic one, and my urging was because I thought he would appreciate how well the story was set up—and the jellyfish spirit animal. After all, my brother’s totemic animal is the slug.

The book does talk a good bit about new scientific research into how the body responds to cold and other stresses. Part of the background that is being reported on is emerging evidence that humans have some degree of control over all sorts of autonomic responses, and that one path to gaining that control is by exposing yourself to stresses that trigger those responses, so as to gain an opportunity to practice exerting control.

One area that’s still disputable is how much of that control is real, and how much of of the observable changes are really a matter of “getting your mind right” about the stressor—maybe all of the changes being measured, such as increased mitochondria turning white fat into beige fat (or turning muscle that preferentially burns carbs into muscle that preferentially burns fat), are merely incidental, and the real difference is just deciding that being a little bit cold isn’t so bad.

Since that was, after all, why I was reading the book, that would not be so bad either.

Last winter, when I got off to a better start than I had this year, much of the change in attitude had been prompted by Katy Bowman’s comments pointing out that the actions your body takes in response to cold (vasoconstriction, shivering, activation of the arrector pili muscles) are all movements—movements that, like squatting and crawling, are done all too rarely these days by most people.

The arrector pili muscles in particular intrigue me. Always described as a left-over muscle that helps animals keep warm by making their hairs stand up for extra insulation, it seems like an awfully complex mechanism to have been so well conserved in humans if that’s all it was for. I suspect they have additional uses. Perhaps the calories burned pulling on hair follicles provides a bit of local thermogenesis that can stave off frostbite without the risk to core body temperature that would result if the area were warmed by blood-flow.

Carny talks a bit about vasoconstriction, suggesting that the pain associated with it is due to the fact that it’s such an uncommon movement in most people. If you train yourself for it, he says, it becomes much less uncomfortable.

Carny also has interesting things to say about non-shivering thermogenesis, which is produced by specialized mitochondria that live in brown fat and beige fat (but also apparently in muscle). In particular, he says that the process of converting white fat to beige fat starts with temperature sensing nerves in the skin! I would have assumed that difficulty maintaining core body temperature would have been the initiator, but apparently not: All you need to do is get your skin cold. This means that going for cold-weather runs will do the trick, which has to be the easiest possible way to do it, because your body produces enough heat while running to scarcely feel cold at all.

Thinking about this sort of thing makes it easier for me to get my mind right with winter.

Also helpful is that we’re getting a few days of less-cold weather. It’s still cold enough to provide the necessary circumstances to induce some cold adaptation, but not so cold that I immediately turn up the thermostat and pull out my warmest parka whenever I need to go outside. In fact, I’ve been making a point of dressing slightly less warmly—choosing a jacket one notch down—than I would if comfort were my only criterion.

I expect that by the time full-blown winter weather arrives, I’ll have gotten my mind right.

On adjusting to the cold and dark

After suffering from SAD for half my life, I’ve had it pretty good the past few years. Last year in particular was actually great—it was like I was a regular person.

This year has not gotten off to a good start, with gloom pressing in on me before we’d even reached Halloween.

With every year being an experiment with n=1 it’s hard to know what makes a difference and what doesn’t, but one thing that occurred to me right away was that last year I had gotten my mind right about the cold (in particular) early.

Two strong influences in the early fall last year were Jackie (who always enjoys the cold weather as an opportunity to wear her woollies) and Katy Bowman (who talks about cold as an opportunity for movement).

In particular, in the run-up to last winter, I came upon not just Katy Bowman but plenty of other natural-movement/ancestral-health folk talking about using cold as an appropriate stressor via cold training.

Many things that people do to induce healthful, adaptive changes in the body are stressors, and produce their beneficial effects precisely for that reason—because the body adapts to tolerate the stress by becoming stronger. Load-bearing exercise makes for stronger muscles and bones. Endurance exercise strengthens the cardiovascular system. Mechanical stresses make for tougher skin. Heat (as in a sauna, but also just from being active outdoors on a hot day) prompts the production of heat-shock proteins that have numerous protective effects at a cellular level, and it turns out that not just heat but all kinds of other stressors, including cold, cause the body to upregulate the production of those same proteins.

Anyway, my point is not that I need to jump into some Wim Hof-style cold training, but that there was a mental shift that I managed to make last year: to view cold as an appropriate stressor that I should revel in, rather than a source of unpleasantness that I should avoid.

This year I haven’t (yet) managed it. Partially I think it was just that the people I follow about this stuff probably feel like they’ve had their say about cold training and have moved on to other stuff, so I wasn’t hearing about it at exactly the right time. Partially I think it was because of the details of the change of seasons this year: We had hot summer weather right into October, then there was a week when it was very rainy, and then it changed to cold, late-fall weather.

Something about missing out on the transition from summer to fall meant that I was taken off-guard. I went from walking shirtless in the sun to wearing a winter coat with no transition except some days when it was too cloudy to get any sun anyway.

However, I am determined not to let this thwart me. It is not too late to get my mind right about the cold.

Gratitude 2017-02-01

Today is the last day this season that sunrise is after 7:00 AM.

Past mid-winter

Some time in October every year I quit being able to get enough sun to make my own vitamin D. Eventually it gets too chilly to go out with enough skin exposed, and even if it stays warm late into the fall, eventually the implacable reality of the earth’s axial tilt means there simply aren’t enough minutes of the day when the appropriate frequencies of UV light shine down where I live.

As a practical matter, this period runs about six months. By early March there’s probably enough UV available, but it’s usually early April before the stars align such that we can take full advantage. We need days when it gets warm fairly early, because the UV is only available for a few hours right around solar noon. (Warmth at 3:00 PM is great, but doesn’t help with the UV until later in the year when the sun is even higher.) We need to get at least two or three of those days each week. (Just two days would probably be enough, if one never had schedule conflicts that kept one out of the sun around solar noon.)

My experience has been this all works out to mean that I need to rely on supplements for my vitamin D needs for right around 180 days per year. With that in mind, I’ve taken to buying two 90-pill bottles of vitamin D each fall.

When I notice—as I say, usually sometime in October—that it has been several days since I managed to get enough sun, I start taking the pills.

Just a few days ago, I finished my first bottle and opened my second.

That means I’ve made it halfway through! Another 85 or 87 days and I’ll be done with the pills and able to make my own vitamin D!

The last few years I was taking 1000 IU pills. This year I upped it to 2000 IU each day. (Not quite as big a change it sounds—I used to eat a lot of children’s breakfast cereals, often supplemented with vitamin D, but since I went low-carb I’m eating a lot less of those.)

It’s still a somewhat higher dose, which I think may be helping. So far this year I’ve only had a couple of days when I found myself glum for no good reason, a bit better than average, I think.

Steven always warns me against imagining that spring starts before April. But soon—less than 90 days now—I’ll once again be able to make my own vitamin D.

In the Conservatory on a gray day in January

I’d been feeling somewhat glum these past two days, so I decided to take steps. Specifically, I paid a visit to the Conservatory at the Plant Sciences Laboratory at the University of Illinois.

It’s a nice space to visit on a winter day. It’s warm. It’s humid. It’s full of plants.

It’s a nice space to visit on a winter day. It’s warm. It’s humid. It’s full of plants.

I’d been meaning to go since before Christmas, but the University’s closure over the holidays made it seem simpler to just wait, and then my glumness made it seem suddenly rather urgent, so today I just dropped everything to go for a short visit.

Longer term, I want to return for a more deliberate visit. I want to return on a sunny day, and see what some bright sunshine does to the space. I want to bring art supplies and spend some time drawing, rather than merely taking a few quick snaps the way I did today.

Longer term, I want to return for a more deliberate visit. I want to return on a sunny day, and see what some bright sunshine does to the space. I want to bring art supplies and spend some time drawing, rather than merely taking a few quick snaps the way I did today.

But today, this is what I had time for, and I think it has been of some help.

But today, this is what I had time for, and I think it has been of some help.

I think the Conservatory, like an art museum, will reward repeated visits.

I think the Conservatory, like an art museum, will reward repeated visits.

In the meantime, enjoy these pictures and imagine that you’re someplace warm and humid and filled with tropical plants.

Gratitude 2017-01-10

Today is the last day this season that sunrise (where I live) is later than 7:15:00 AM.