Five years ago made a plan to spend the winter trying to build the strength I thought I’d need in order to be successful at (and enjoy) training for parkour. To keep the whole thing manageable, I chose just four specific exercises to work on. And to keep myself accountable, I described a “success” condition to let me know if I had accomplished each one. (I documented my plan here: strength training specifically for parkour.)

I wasn’t successful at meeting most of those goals after that first winter, which was discouraging, and I kind of quit tracking my progress on those metrics after that. But in my preparations for writing my “Movement in 2020” post, I happened upon that post—and was surprised to see that I had pretty much accomplished it!

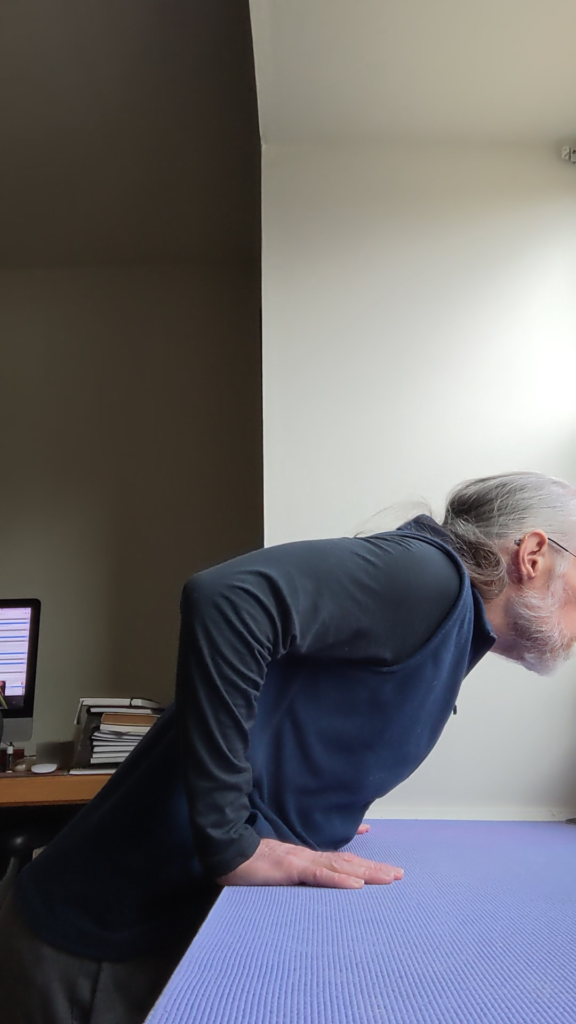

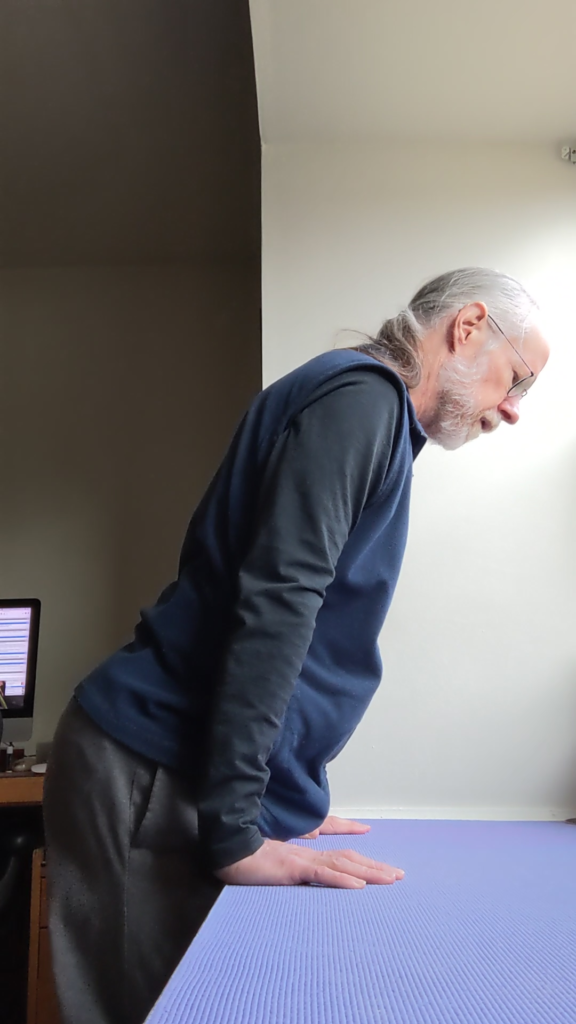

Squatting

Squatting is an important transitional posture, into and out of ground movement, and into and out of jumps. (It’s also a basic human capability, but one that requires a degree of strength and flexibility that most westerners no longer have.)

Five years ago I could only just barely squat, and then only when nicely warmed up. Since then I have worked on my squat in a dozen different ways—working on ankle mobility, hip mobility, and strength up and down the posterior chain.

My original benchmark was:

Success will be when I can get all the way down with a straight back, and then use my hands to manipulate things that are nearby.

I can report a considerable degree of success! I can get down into a deep squat, and I can linger there for tens of seconds at a time. I’m now working on improving my mobility while in a squat (looking to each side, up and down, reaching up and down, etc.).

Here’s where I was back then, and where I am now:

Toe Stretches

Early on my efforts to get better at various natural movements were significantly hindered by a lack of toe flexibility. My toes literally did not bend back at all.

This was actually a long-standing problem. At least as far back as college my martial arts instructors warned that I needed to pull my toes back or I’d hurt myself if I executed the kicks I was learning. But none of my martial arts instructors had even the tiniest bit of advice on how I might acquire the capability to pull my toes back.

Five years ago I came up with my own idea. I’d get into quadruped position while keeping my weight back on the balls of my feet (meaning that my knees had to be rather higher than ideal), then I gently worked to lower my knees toward the floor. That helped me make some progress.

A couple of years later, Ashley Price suggested an excellent exercise involving using a half-dome to let me gently flex my toes back. I’ve been doing that exercise almost daily since then.

My original benchmark was:

Success will be when I can keep my weight back on the balls of my feet and still get into position for things like planks, push-ups, and lunges.

On that I can report complete success. The only thing that still eludes me is the quasi-martial arts move where you sit seiza (kneeling with the tops of your feet on the floor) then pull your toes back and tuck them under, shift your weight to the balls of your feet, rock back into a squat from which you can stand up. This is useful if you want to move from kneeling to standing while simultaneously drawing a sword, but is perhaps not particularly important beyond that.

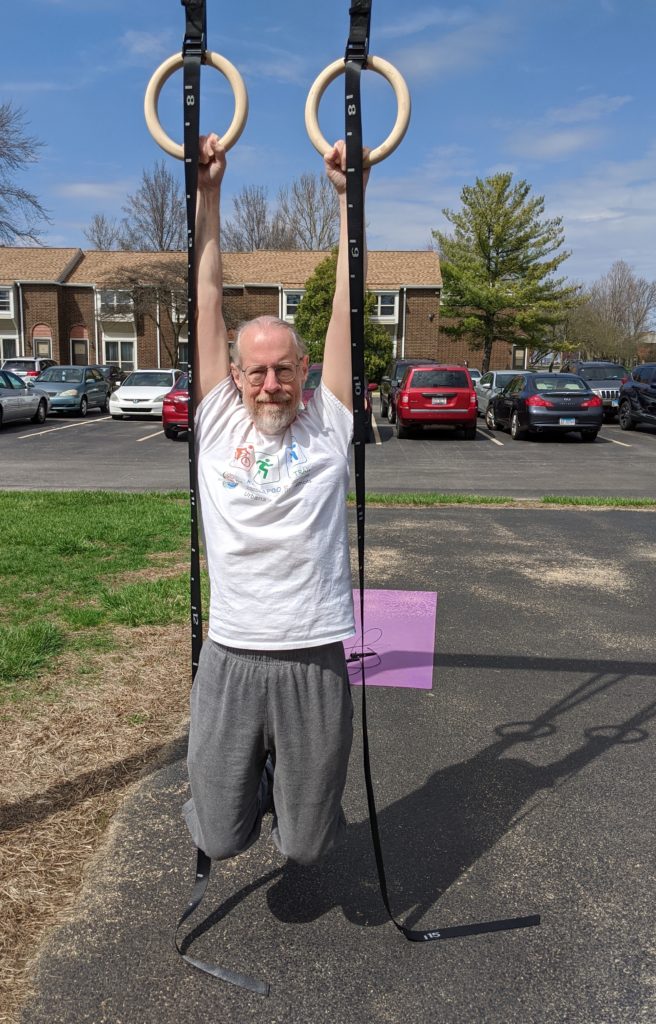

Hanging

The ability to hang by your hands is crucial for many parkour moves.

Hanging was one of the things I worked on early, and made quite a bit of progress at, working up to being able to hang for a minute no problem. At about the same time I briefly managed to do a chin-up. But until this year I hadn’t done a pull-up since I was in elementary school.

Since I redoubled my efforts on pull-ups back in April or so, I’d largely quit working on hanging endurance, and it has somewhat slipped away—I can do 30 seconds, but a recent attempt at a full minute fell short. Similarly, although I can hang briefly from one hand, I can’t do what I could do a few years ago.

My original benchmark was:

Success will be a single pull-up in good form from a dead hang.

And at that I have succeeded! I can do a pull-up! In fact, on a good day I can do pull-ups in sets of three. Even on a less-good day, I can manage three sets of one pull-up.

Wall Dip

The wall dip is another foundational move for parkour. You use it to get on top of a wall or other structure.

The village where I live seems to have a terrible dearth of chest-high walls (unlike campus, which has lots), so it has been persistently difficult to get in the practice I need, and doubly so during the pandemic.

What I’ve been doing instead this year are ring dips.

Ring dips are actually much harder than wall dips, because the rings are unstable, so you have to stabilize them yourself. As I sat down to write this, I was worried that the limitations of those stabilizing muscles might have kept me from fully training the pushing muscles for the dip itself.

So over the last few days I’ve checked for that, using the edge of my window seat as a wall for practice. (It’s not perfect, because it’s too low, so I have to tuck my legs back to keep my feet off the floor. That configuration doesn’t precisely match the way you’d do a wall dip in parkour, but it does let me fully test the basic pushing motion.)

My original benchmark was:

Success will be when I can do a dozen or so wall dips with good form.

On three different occasions this week I’ve done at least a dozen wall dips, so I can call that one accomplished as well.

Assuming I can keep it together to do at least some maintenance training during the winter, I can enter the spring with a solid base on which to pick up my parkour training!

I’ve spent the past 5 years working to recover my ability to rest in a squat. Not quite there yet, but getting closer. (Photo by Jackie Brewer.)

I’ve spent the past 5 years working to recover my ability to rest in a squat. Not quite there yet, but getting closer. (Photo by Jackie Brewer.)