I generally don’t think of myself as a scary person, but there are a few times when people have reacted in a way that made me think I frightened them. Here are three that made enough of an impression on me that I remember years later.

Out of fries

When I was about 15 or 16, my mom took me to a restaurant near my high school. We gave our order, but just a minute later the waitress—a girl perhaps two or three years older than me—returned to say that they were out of french fries.

Using my overly dramatic voice of mock outrage, I said, “Out of french fries!?!?”

And the waitress cringed.

I did my best to console her—I assured her that a burger with no fries would be fine—but I felt terrible. It was the first time in my life that I comprehended that I’d frightened someone.

Car door locks

In college I worked at the computer center, and one year I spent a Christmas break helping to bring up a new version of the operating system. In those days, the college just had one computer, which did both administrative stuff (like printing checks and addressing letters to alums) and stuff for students and faculty. The new OS was not yet trusted to handle the administrative tasks, so I was starting work after the administrative users of the computer finished up at 5:00 PM, and then heading home late at night, often after midnight.

It was a long walk to where I was staying, so I took the shortest route I could. One stretch had me cutting at an angle through a parking lot, reaching the next street in the middle of a block.

One day I stepped out of that parking lot, onto the sidewalk—and found myself right at the door of a car with a African-American woman and a couple of young children inside. The woman, seeing me come out of nowhere (not down the street from ahead or behind) right up to her car, hurried to lock her car doors as quickly as possible.

I have always been a little ashamed that, for just a moment, I thought, “But I’m white!” as if that should have made a difference.

Leather jacket and motorcycle helmet

One of my coworkers helped teach a motorcycle safety course and convinced me to take it. I bought a helmet (required to take the course), a leather jacket, got my motorcycle endorsement, and in about 1990 or 1991 I bought a motorcycle and started riding it to work.

One day I ran a mid-day errand at the mall, and decided to stop at fast-food restaurant for lunch. That particular restaurant had railings set up to encourage people to form a single line, and I took my place at the end of the line.

The next time the person at the front departed, the people in the line moved forward a bit too aggressively. Finding themselves bunched together, the people at the front of the line moved back, forcing the people behind them to move back as well.

The person in front of me took a step back without looking, and bumped into me, hitting the motorcycle helmet I was carrying in my hand. Having bumped me, he turned to look at me—and lurched away again from the terrifying visage of a guy in leather jacket with a motorcycle helmet, bumping into the guy ahead of him, producing a whole second cycle of to-ing and fro-ing for the whole line.

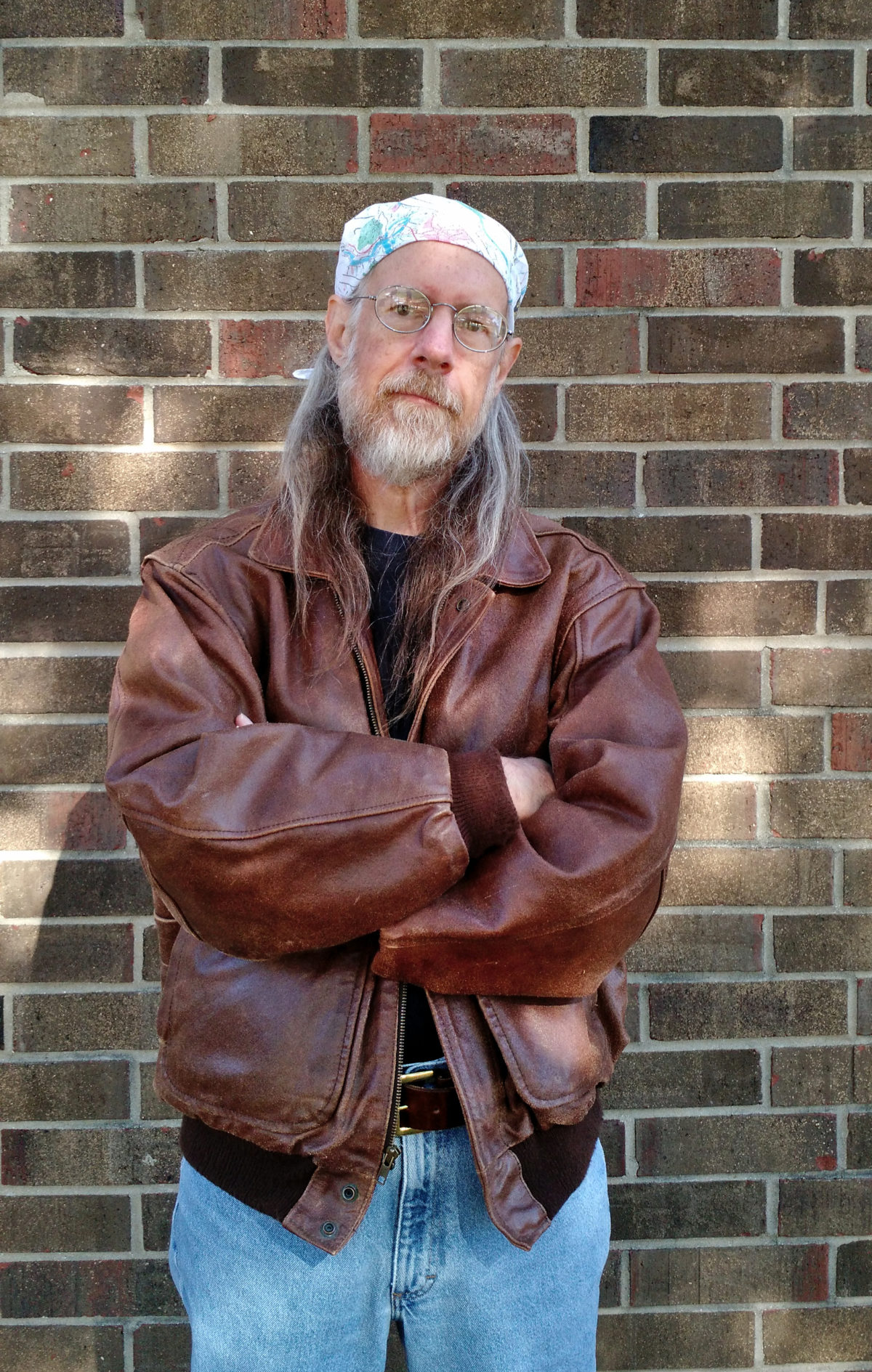

Even with the helmet and jacket, I did not think of myself as a scary biker dude, but the guy ahead of me in line sure did. (The image on this post has me wearing that same leather jacket. I got rid of the helmet long ago, so for the photo I’m wearing my most biker-dude bandana, printed with a topographical map of the Appalachian Trail.)

Being dangerous

There are several factors that go into making someone dangerous. In particular, there’s the difference between having a capability to do harm versus having an inclination to do harm.

Absent actual knowledge, other people have to rely on markers for each of these things. A raised voice, a sudden appearance in an unexpected place, the dress and accoutrements of a certain category of people all can serve as such markers.

It is a commonplace of action fiction that those who are themselves dangerous can spot the difference between someone who is actually dangerous versus those who merely pretend. I don’t think a fictional action hero would have been fooled for a minute in any of those incidents.

I’ve begun to notice, though, that there’s some truth to the idea that you can tell the difference between those who are dangerous because they have skills versus those who are dangerous merely because they are volatile. Thanks to my taiji practice (especially teaching taiji) I’m beginning to notice a few of the things that go into the calculation—being balanced, being centered, being ready to move.

It’s actually kind of unhandy—noticing such things has made it harder for me to put my attention elsewhere—making it harder to play Ingress, for example.

I don’t think of myself as scary, and I certainly wouldn’t want to project an aura of menace all the time. But being able to project menace is an ability that probably has its uses in real life as well as in fiction.

I very much recognize the position of privilege I’m speaking from here. More than a few people have died recently, because someone with a gun thought they were menacing—even when they were running away, or standing with their hands up, or lying down on the ground with their hands up.