A couple of weeks ago the New York Times linked to a new study on age-related declines in human movement. It’s an odd study, but not because of the result (which shows that children start moving less at age 6), because that seems entirely predictable to me, despite the general understanding previously having been that the decline started in adolescence.

Rather, what makes the study seem odd to me is the weird blind spot the researchers seem to have about when and how organisms (including humans) choose to move.

In the study itself the researchers make clear that they had considered the obvious presumption—that kids start moving less when they start going to school: “The overt explanation for this earlier decline could be the increased sitting times due to school.”

The blind spot I’m talking about is presented in the next sentence, where they immediately qualified that:

However, time-specific analysis of [physical activity] has revealed that in addition to the increased [sedentary behavior] during school hours, there was also a distinct decline on weekends, out-of-school days, and during lunchtime.

Schwarzfischer P, Gruszfeld D, Stolarczyk A, et al. Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior From 6 to 11 Years.Pediatrics. 2019;143(1):e20180994

What’s weird and horrifying is that they make that statement seemingly without it occurring to them that forcing children to sit still for hours on 5/7ths of the days of the week might affect their behavior on the other 2/7ths of the days.

Right off the top of my head I can think of four obvious reasons that would be true:

- The required behavior in school normalizes the behavior of extended sitting.

- Even a few weeks of enforced extended sitting will result in the kids becoming deconditioned aerobically, making physical activity more difficult and less appealing.

- Extended periods spent in any static posture—especially the static posture of sitting—will begin the process of reducing their range of motion (they’ll pretty quickly lose the ability to squat, for example), again making physical activity more difficult and less appealing.

- The addition of “physical education” to the kids’ daily schedule sets the pattern of replacing movement with exercise—a time-bound, regimented activity which attempts to pack the health benefits of a week’s worth of movement into just a few hours. (I’ve written about this before.)

Just one instance of this blind spot is bad enough, but it shows up again in a key reference. The researchers say that it is accepted that physical activity declines with age: “A natural and biologically determined decline of total [physical activity] throughout the life span seems likely.” They support that assertion with a couple of references, one of which looks specifically at movement in non-human animals.

Unfortunately that study (Ingram, D. K. Age-related decline in physical activity: generalization to nonhumans. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc., Vol. 32, No. 9, pp. 1623-1629, 2000, which is sadly behind a pay-wall.) has exactly the same blind spot: All the animals studied were captive animals. That study looked at how animal movement varies when an animal is moved from its “home cage” to some other cage. I can’t say I’m the least bit surprised the behavior of those captive animals closely resembles the behavior of children moved from home to school and back again.

I would be very interested in studies that included some free-range animals. (Which isn’t something I can do, but which seems at least possible now that accelerometers are cheap.)

Of course school isn’t the only factor that inhibits children from moving more. The restrictions on self-directed play so well documented by Lenore Skenazy of Let Grow no doubt feed in as well.

So it would be great if there were studies of movement in free-range kids as well.

The final weird and horrifying thing isn’t anything new, but is something I hadn’t really been aware of before: The assumption that an age-related reduction in movement is “natural and biologically determined,” has led directly to public policies that normalize it:

This decline is also represented in recommendations from the World Health Organization (WHO): preschool-aged children should accumulate a minimum of 180 minutes per day of total [physical activity], children and adolescents (4–17 years old) at least 60 minutes per day, and adults only a minimum of 30 minutes per day in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA).

To which I say, “Argh!”

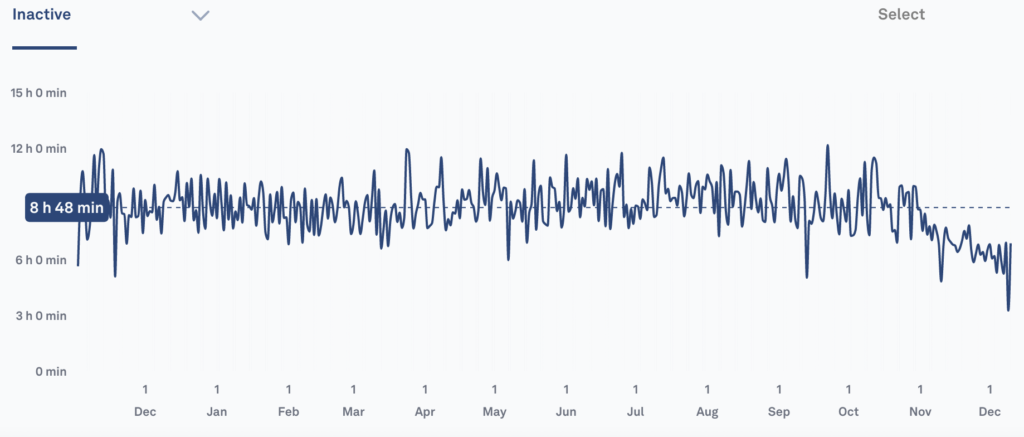

I probably wouldn’t be so struck by this if I weren’t already tracking my own movement. (Cheap accelerometers again.)

For some time now I’ve been working to a goal of 105 minutes of movement per day, and over the last few weeks I’ve come pretty close, averaging just over 102 minutes of movement per day, according to Google Fit. (This number, based primarily on steps, somewhat underestimates my movement. In particular it gives me almost no credit for the time I spend teaching taiji, because although there’s plenty of movement, there’s not much stepping.)

The WHO recommendations make me strongly motivated to upgrade my goal for movement to 180 minutes per day.

Why should kids under 6 get all the fun?

(The image at the top is topical only in that it is is a photo from our afternoon walk yesterday.)