Zone-2 cardio has been having its moment. That comes from a lot of sources, but unfortunately a big one is Peter Attia. I say “unfortunately,” because Attia seems to have a weird, compulsive sense that zone-2 cardio work needs to be, I don’t know, pure in some way, rather than just being enough to promote good metabolic health.

Attia suggests that you do your zone-2 work on a treadmill, stationary bike, or rowing machine, so you can be in control of your effort level at all times. Then you can just get into zone 2 and stay there for 45 minutes.

I think this is crazy, and not just because 45 minutes of steady-state activity on a treadmill or stationary bike would be excruciatingly boring.

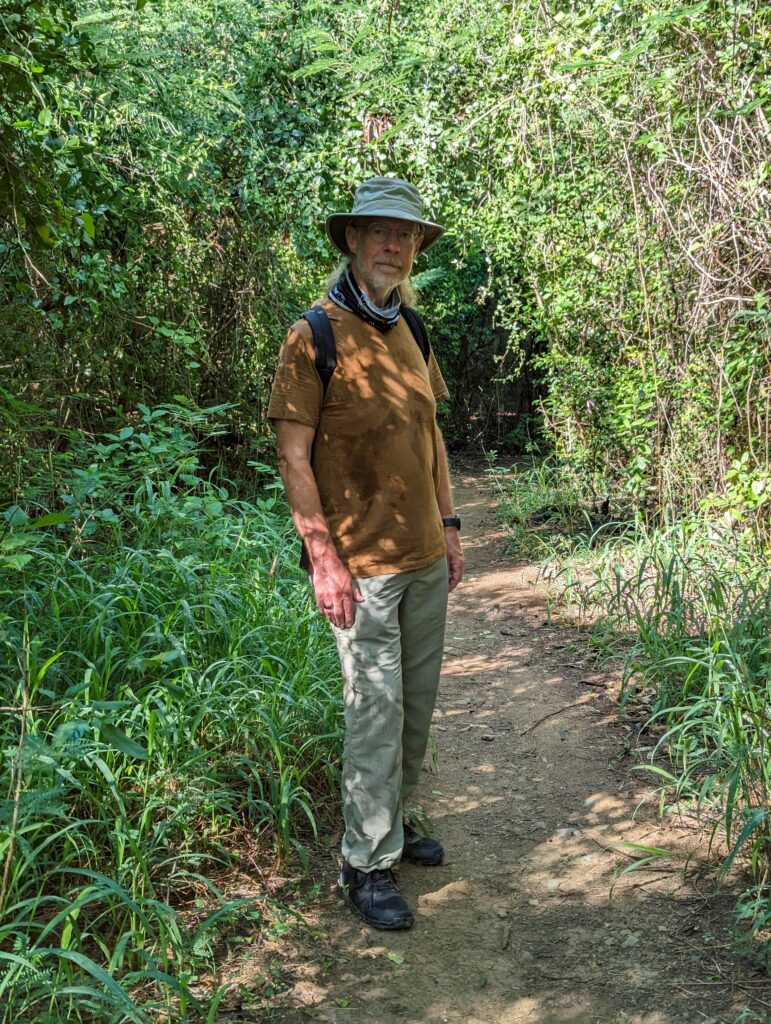

I do my zone-2 cardio with a mixture of walking my dog, running, and occasional hikes. Walking the dog isn’t perfect, because the dog keeps stopping to get in her sniffies, and no doubt my heart rate drops out of zone 2. Running isn’t great, because my heart rate probably spends a lot of time in zone 3 or zone 4. A lot of it is zone-2—at least, I can talk while I run, which is one of the tests for zone-2. (I run very slowly.) The hikes are probably perfect zone-2 cardio, but are a big time commitment in a single day.

Attia suggests that you optimize your cardio workouts by getting 3 hours a week of zone-2 cardio, which can optionally be divided into 4 45-minute workouts. And I’m sure that’s fine. But I suspect that getting in a couple of runs a week, along with a good bit of dog walking, is going to check the zone-2 cardio box no problem.

My theory (and I am not an MD, nor even a PhD in exercise physiology, but still) is that this is fine. You don’t need to get 45 minutes of pure zone-2 cardio to be metabolically healthy.

As I see it, the test for whether you’re getting enough zone-2 cardio is whether or not you can engage in a moderate level of exercise for an extended period—a 3-hour hike, let’s say. If you’re metabolically healthy you can go on and on at a moderate pace, because you’re doing it almost entirely aerobically.

If you can do that, you’re getting enough zone-2 cardio, regardless of whether your sessions are 45 minutes long, and regardless of whether they add up to 3 hours a week. If you’re not metabolically healthy, even going at a moderate pace is going to push you into anaerobic metabolism, which will quickly become impossible to maintain.

It probably is true that you need to get in 3 hours a week if you’re going to be able to go on long, long hikes. But the idea that they need to be pure zone-2 sessions, rather than mixed sessions at all different levels of intensity, is just crazy.