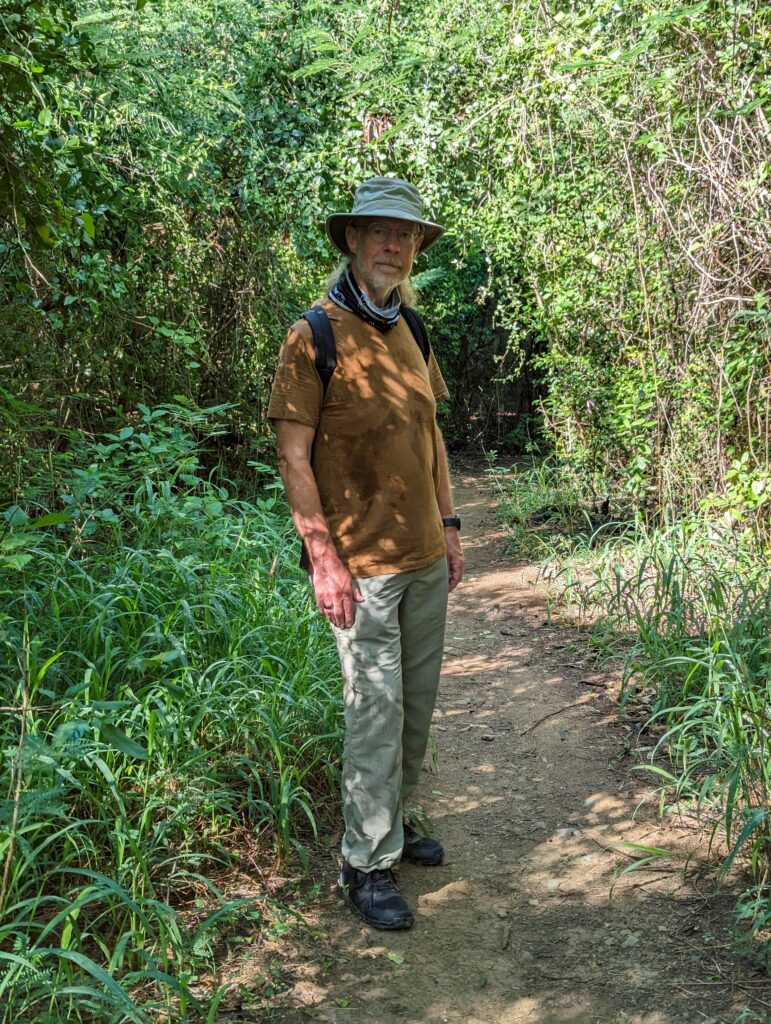

For much of my life I thought that the key to losing weight was just exercising more. Especially in the mid-1980s, when I lived in Utah and California, I’d get out for some long hikes in the mountains and deserts and think, “If I could just do this all the time, it would be easy to maintain a proper weight.” That turns out to be both true and false.

The fitness influencer types like to say things along the lines of “You can’t outrun your fork,” meaning that you simply can’t burn enough calories to get ahead of eating way too much. I knew that wasn’t completely true. Read about any long-distance endurance athlete (ultra-marathoner, Tour de France rider, etc.) and you’ll have a window into really extreme efforts to eat enough just to keep going, let alone enough to recover for the next day’s effort.

I also have a slightly more ordinary example. A couple of guys I knew tried to bicycle around Lake Superior and Lake Michigan, and had to abandon the effort halfway through, because their riding (100+ miles per day) burned so many calories (perhaps 5000 calories on top of their basal metabolic rate, so maybe 7500 calories per day total), they ran out of money for food.

It’s tough to eat 7500 calories per day even without the financial limit, so it seems like, if you have all day to do nothing but exercise, and the will to exercise hard for several hours a day, perhaps you could “outrun your fork.”

Recent research shows that this is not the case, except in the very short term. People who are very active all day, like hunter-gatherers (but also subsistence farmers, and laborers of other sorts), burn more calories than people who are sedentary all day, but only modestly more.

A recent study showed that among of Hadza people, activity was almost insignificant as a predictor of total energy expenditure. They were remarkably active, but their calorie consumption was pretty ordinary. The study suggests that body size is just about all that matters

In that study, average total energy expenditure among Hadza men was 2649 calories per day. The average is higher among western men, but only because their body size is greater. (Hadza men averaged 50.9 kg (112 lbs), while Western men averaged 81.0 kg (179 lbs). Differences in BMI are more stark, with Hadza men having a BMI averaging 20.3, while Western men’s BMIs averaged 25.6.)

The point here is that it seems like your biology is attuned to wanting to eat 2600 calories and wanting to burn 2600 calories. (Adjust for frame size. It seems the Hadza men averaged about 5′ 2″.) You can be sedentary, under-eat to match, and not gain weight, but it’s not in tune with what your body wants, so you’ll be hungry all the time, as well as having all the side-effects of under-movement.

You can also try to exercise enough to burn more than 2600 calories, but it seems that as soon as you go over that level, your body starts trying to compensate—turning down whatever is easy to turn down, such as your immune system, and muscle-building system.

That doesn’t happen immediately. If you go on a century ride you will burn the extra 5000 calories that simple arithmetic would suggest. That would probably continue if you went on a three-day bicycle tour. But pretty quickly—probably just in a week or so—less-essential body functions would ramp down (and of course fatigue would ramp up) bringing your total consumption back down toward 2600 calories.

You can see how this would work well for hunters. You go for a hunt one day (or two or three days), hiking or running for miles, finding prey, tracking it, and finally killing it. Then you (and your whole tribe) have lots of food to eat for a day (or two or three). During extended periods of excess activity maybe your immune system and muscle-building system ramps down, but then during periods of ample food and less activity, maybe it ramps up extra, allowing for full recovery.

Consuming more calories than you burn for more than a few days, however, quickly leads to problems. Increased fat storage is probably the least of them. Insulin resistance is another. Systemic inflammation is another. Those extra calories will go into the things that get turned down when you’re extra-active, such as the immune system. I don’t know that there’s any evidence, but an obvious possibility is that a lot of auto-immune disorders are just an immune system that never gets turned down because people are never active enough to burn more calories than they eat, if only for a day or two.

I think it’s true that you can’t out-exercise excess calorie consumption. However, you can definitely under-exercise—and trying to under-eat to match that will also cause problems. Humans evolved to thrive with an ideal level of activity.

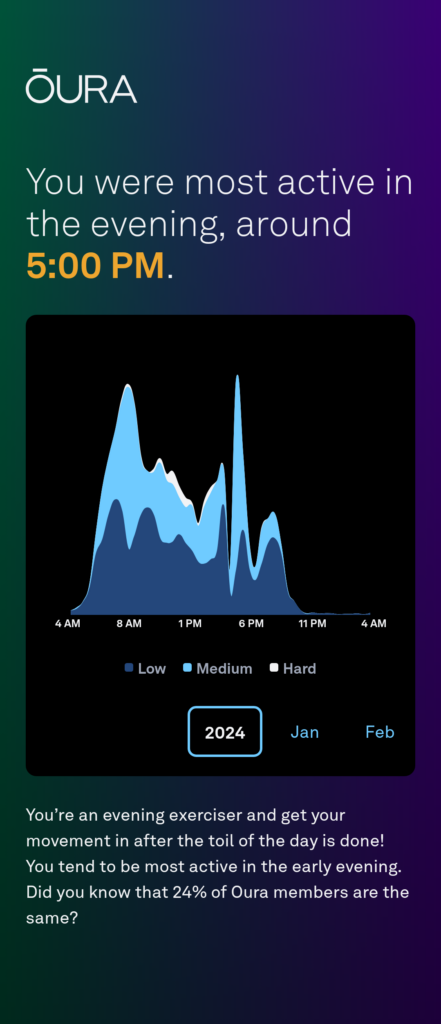

It’s also true that you don’t need to hit that particular level of activity and food consumption every day. In fact, I’m sure you’d be better off to be moderately active most days, and then very active 1–3 days a week. My long-ago dream of being able to hike 10–15 miles every day and then eat all I want turns out to be a terrible idea. Rather, you want to walk 5 or 6 miles most days, and then hike 10–15 miles just once or twice a week. (Feel free to swap in bicycling or rowing or whatever you like for the long days of vigorous activity, although you probably want to keep in the basic walking if you possibly can.)