This handsomely lichenous tree is right across the street. 📷#mbfeb

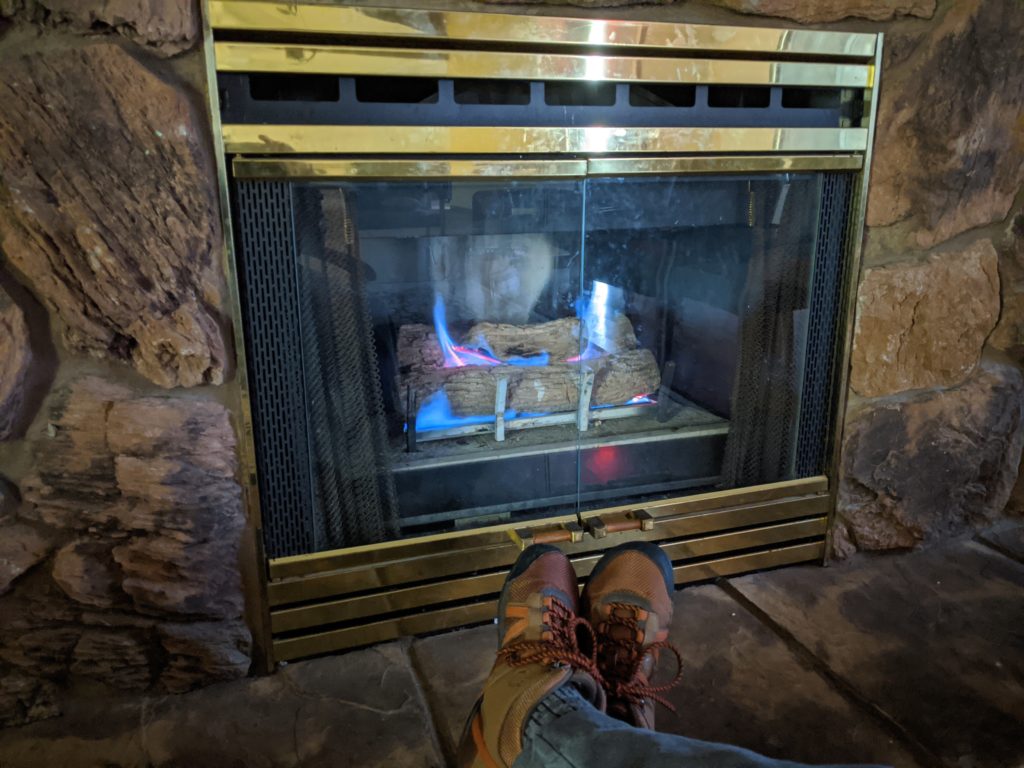

After Steven suggested that hanging out near a fireplace would help with SAD I hunted all over Champaign-Urbana, but somehow it never occurred to me that there’s a fireplace right in the Winfield Village community room!

Since reading a couple of weeks ago about the importance of blue places for both physical and mental health, I’ve been trying to spend a little more time near water, and to pay attention when I’m there.

Today Jackie and I took a short walk along the little creek that runs just south of Winfield Village. It’s really a spectacular amenity that I don’t appreciate nearly as much as I should. (I spend a lot of time admiring our little prairie and our little woods, but I mostly just cross the creek itself with scant notice—nowhere near what it deserves.)

Perhaps you can help me catch up on appreciating our creek. Is it not admirable?

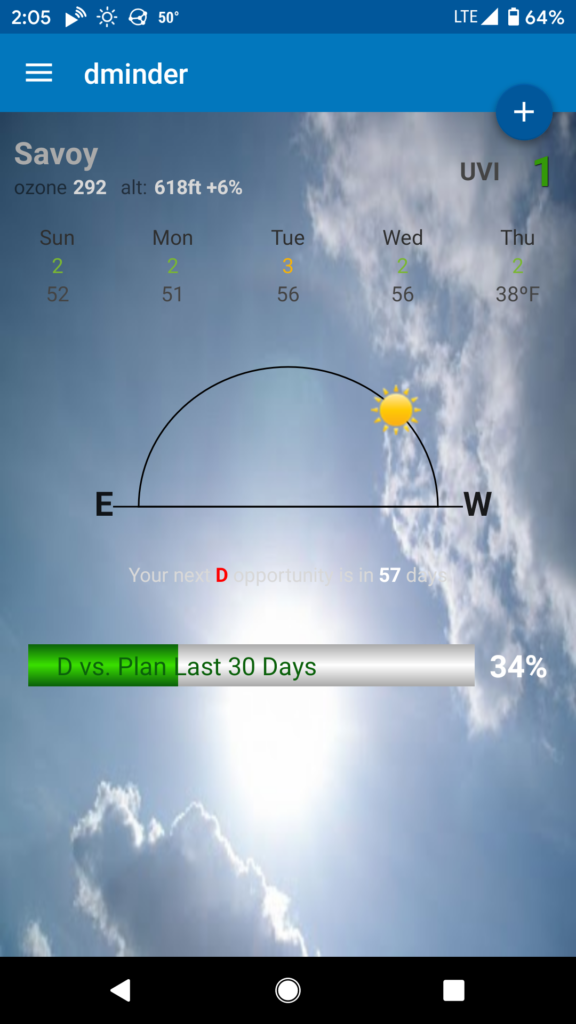

It got me some vitamin W for the water and some vitamin N for the nature, but sadly no vitamin D. The vitamin D window has closed, and won’t open again for 57 days.

I make an effort to get out into nature as often as possible. With our little prairie and woods nearby, it’s possible almost every day. Larger natural areas—Forest Glen, Fox Ridge, Spitler Woods, etc.—are within easy driving distance.

With my focus having been on nature for a long time, I was interested to read this piece in The Guardian:

In recent years, stressed-out urbanites have been seeking refuge in green spaces, for which the proven positive impacts on physical and mental health are often cited in arguments for more inner-city parks and accessible woodlands. The benefits of “blue space” – the sea and coastline, but also rivers, lakes, canals, waterfalls, even fountains – are less well publicised, yet the science has been consistent for at least a decade: being by water is good for body and mind.

Source: Blue spaces: why time spent near water is the secret of happiness

We do have some water right here where we live. There’s the little creek that runs behind Winfield Village and a couple of little detention ponds, and they do have some wildlife. I often see turtles, snakes, groundhogs, and many sorts of birds. I’ve occasionally seen mink, coyotes, and bald eagles.

I do feel the lack of a beach. The closest is Indiana Dunes, but it’s nearly 3 hours away. I’ve done it as a day trip, but it makes for kind of a long day.

The article makes for a good reminder to be sure to include blue when you’re making sure you get out into the green.

There’s a song I half-remember with the line, “I’ve had the patience of a tree,” so that was my first thought when @macgenie proposed “patience” as the first prompt for her convalescent photoblog challenge.

Jackie and I went for a nice walk yesterday, through the prairie and woods next to Winfield Village. We walked about four miles altogether.

Toward the end of the walk I paused to retie a boot, and found that my back was really tight. Bending down caused pain in my sacroiliac joints.

It was odd because it was a familiar sensation, but an old familiar sensation. I used to feel that pretty often on a long walk, but I hadn’t felt it lately. Without really thinking about it, I had attributed the change to general improvements in fitness and flexibility. But here after a fairly short walk that old pain was back again.

I was briefly puzzled, but realized right away what had happened: Because the walk was going to be wet and muddy, I’d worn my old heavily lugged goretex hiking boots.

These used to be my main boots; they’re the ones I wore on my 33-mile Kal-Haven Trail hike. I’ve kept them because I haven’t found a satisfactory pair of waterproof minimal boots, and I’ve worn them right along over the three or four years I’ve been transitioning to minimalist footwear, whenever I needed waterproofness or a heavily lugged sole. But they have the big downsides of non-minimalists shoes: Their thicker heel jacks up my posture, and their rigid sole keeps my feet from adapting to the terrain.

It might not be just the footwear. The trail was muddy enough that every step was a bit of an adventure—my foot would sink into the ground, but it would sink a different amount each step, making it hard to establish and maintain a consistent gait. I wouldn’t be surprised if that didn’t play into making my back feel a bit wonky after a couple of miles.

But clearly it’s time to retire these old boots and find some waterproof minimalist boots with sufficiently lugged soles to handle some short, steep hills on a muddy trail.

If you’ve got any suggestions, I’d be glad to hear them. Comment below, or send me email! (Email address on my contact page.)

I used to play on the monkey bars all the time when I was a kid. My mom encouraged it. She knew it built upper-body strength, and that the ability to traverse monkey bars was an important capability for any human. (She could traverse monkey bars herself, when I was a boy.)

I quit doing the monkey bars, probably when I was college age, and quickly lost the capability. Then for three decades would have been afraid to even try, because I’d definitely have hurt myself. A few years ago I wanted to regain that capability, so I started looking for monkey bars to practice on, and found that they’ve gotten quite scarce. Many playgrounds don’t have them at all.

Winfield Village has a playground in every quad, but the only playground with any sort of monkey bars is the big one close to the office, and it has a rather strange curving monkey bar that over the course of 5 rungs makes a 90° turn—a particularly challenging version. (Like most these days, this one has weird triangular bars hanging from a single support, rather than a series of rungs supported on both sides.)

The reason for both the near disappearance and the switch to triangular bars seems to be that monkey bars are “dangerous.” Many playground safety experts recommend that monkey bars be excluded from playgrounds altogether, and I think the weird shape is designed to make them harder to climb on top of, in the hopes that kids would then not do so.

I spent a chunk of yesterday afternoon at an “alignment play day” with folks from CU Movement (and kids), getting some hanging and balancing and barefoot walking on various textures. One thing I did was traverse the monkey bars at Clark Park in Champaign—an old-style set of monkey bars, rather like the ones I remember as a kid.

One of the kids in our group—small enough that it was a challenge to reach the next bar, and at a height that the experts would no doubt claim was “too high” for a kid of that size—did the monkey bars, and then immediately wanted to climb on top of them. He asked for help getting on top, which his mom declined to provide—except that she pointed out that one of the supporting poles could probably provide the necessary foot purchase for him to get on top on his own. And he did manage to find two ways to get up there. Having gotten up there, he decided against traversing the top of the monkey bars, and simply swung back down under them.

A new school of thought is emerging (finally!) that “dangerous” playground equipment offers valuable opportunities for kids to do exactly what this boy did: evaluate a hazard and decide how much risk was appropriate. The only way to learn to make that sort of evaluation is to actually practice it. Making playgrounds so safe that children cannot hurt themselves reduces their opportunity to develop a good sense for what is safe and what is dangerous, and what is and is not within their capability.

It has also made it a lot harder for me to find a set of monkey bars to practice on.

I crossed the monkey bars three times in the afternoon, but I forgot to attempt my next big trick: Cross from one end to the other, turn around (without putting my feet down) and cross back again.

I’ll do that next time.