I want to talk about something that Patrick Rothfuss does very well. It’s really a small piece of his vast array of skills—the lyrical language, the masterful worldbuilding, the high adventure, the compelling characters—but I think it’s integral to the way he manages to hit those powerful emotional high points over and over again.

His characters learn. They learn all the time.

Most stories are about characters who learn. Not all: James Bond doesn’t grow and change; a lot of older episodic fiction was structured so that characters returned to the status quo ante by the end of every episode. But most stories are about a character who needs to learn better. The story leads the character through a series of events that somehow provide the needed education, and at the end the character behaves in such a way that we understand that the necessary lesson has been learned.

A very short story can be not much more than this. In a longer story, though, the result is often quite unsatisfactory, especially if the cycle—flaw leading to wrong action leading to suffering—is repeated. By the time we get to the end of a story like that, I no longer care much whether the hero will learn to care about other people or overcome his addiction or stop blaming himself for some long-ago mistake.

One way for the novelist to handle this is to have other problems for the hero to overcome. If the hero is busy saving the world, it’s easier to accept that he’s not overcoming his personal problems as quickly as we’d like. When, in the end, he does overcome his personal problems—especially when doing so is also key to saving the world—it can be very satisfying. But to make that work, the reader has to be kept aware of the flaw, which means once again we have repeated cycles of flaw, wrong action, suffering. Cycles that I find tedious and frustrating.

The other, better, way for the novelist to handle this is to have the hero make incremental progress in learning what he needs to learn. It’s both more realistic and more interesting. The problem is that it tends not to lead to the sort of rising action that makes for a satisfying climax. Partial learning leads to less wrong action which leads to less suffering—this is not stuff from which it is easy to form a compelling climax.

This is where Patrick Rothfuss displays incredible virtuosity. His characters (not just the hero, but also all the characters around him) learn stuff all the time. Because they learn stuff, they make fewer mistakes, they cause less suffering for themselves and the people around them. And yet, tension continues to rise. How does he do that?

Part of it is that, as they learn, their capabilities grow, and as their capabilities grow, their mistakes have larger consequences.

More important, as their capabilities grow, they choose to take on greater challenges. That’s realistic and interesting, but in less capable hands it often leads to stores that are too episodic. (Rothfuss overcomes that through the structure of a wrapping story, that lets us see early on that all the episodes are leading somewhere.)

I really want to learn to understand this better, because this feature—characters learning— creates repeated mini-climaxes. And here is where the virtuosity becomes manifest.

In inferior stories, the reader can plainly see what the hero needs to do—quit running away from his problems, quit being so full of himself, quit acting like a jerk, whatever—but has to wait to the end of the story for the hero to figure it out. In The Name of the Wind and The Wise Man’s Fear, by the time the reader understands what the character needs to do, the character is well on his way to understanding it as well. And when the character does learn (and demonstrates that learning by making better choices, and the better choices lead to better results), the reader feels the same glow produced by the climax of a great story. Over and over again.

And yet, tension continues to rise. Virtuosity. I want to learn it.

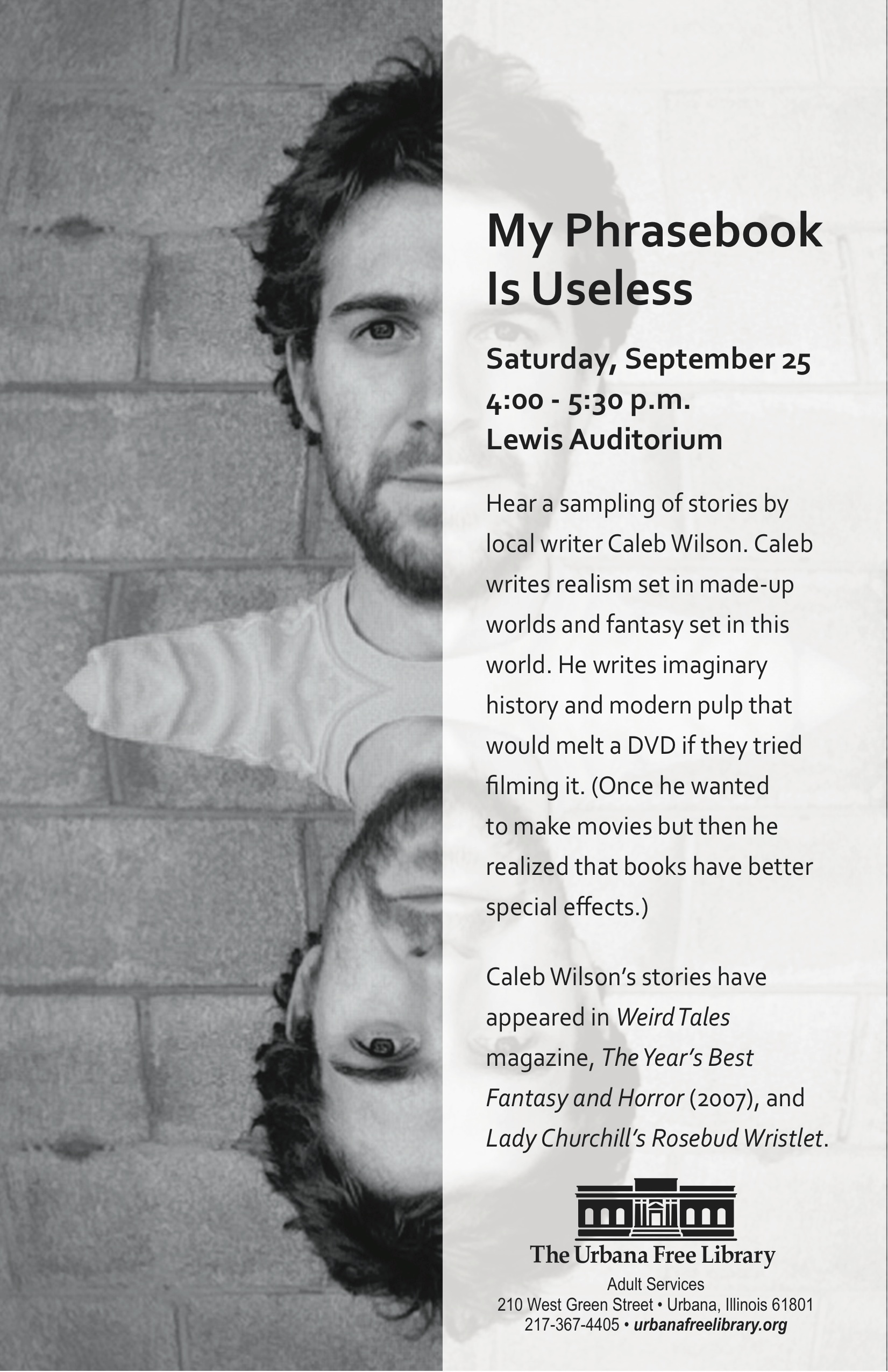

(Oh, and just as an aside: I once won a free book by writing the winning caption for this picture of Patrick Rothfuss.)